Michael - Every other Thursday

For many years I’ve had a (very much layman’s) interest in things like animal perception and consciousness. Maybe this was generated to some extent by my interest in image processing and analysis, which naturally links to the way the human eye works and why it works that way. We are all familiar with the ways in which our brains represent images producing all sorts of changes to what is actually before our eyes. Some of these are almost games, like the apparent 3D vision images called stereograms.

|

| See the shark? Look closer |

Here's a

really important one.

|

| Edges? |

You notice how the edge of each rectangle has been emphasized in the image so that we can easily see where one rectangle ends and the next starts. Well, no actually. Your brain is doing that. We care about identifying things, and so our inbuilt processing automatically does some edge enhancement to help.

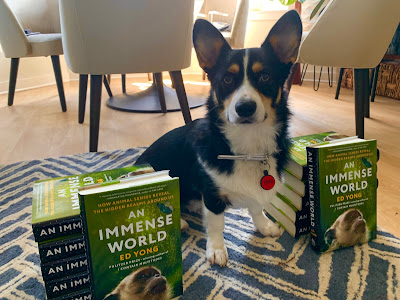

What is really fascinating is speculating on what animals see, what their image processing is, and why. It turns out that there’s a big group of biologists who study these things and publish results in specialist journals. However, one of them is also a talented writer who has written a mind-blowing book for the general reader about how other creatures perceive the world and why. His name is Ed Yong and his book is called An Immense World – How Animal Senses Reveal the Hidden Realms Around Us. |

| Ed Yong's corgi Typo with copies of the book |

If I’ve made the concept sound dry, that’s my fault, not Yong’s. The Times called the book "Extraordinary" and The Guardian said it was "Magnificent". As for me, I can’t put it down. It made its way to the Sunday Times best-seller list so I can’t be alone in that.

To start at

the beginning, it’s obvious that all creatures share the same physical universe.

But, as Yong puts it, “Earth teams with sights and textures, sounds and

vibrations, smells and tastes, electric and magnetic fields. But every animal

can only tap into a small fraction of reality’s fullness. Each is enclosed

within its own unique sensory bubble, perceiving but a tiny sliver of an

immense world.” This sliver is called its umwelt – the creatures perceptual

world.

Even this starting

point is fascinating, especially when we realize that humans are no different

from other species in this constraint. In fact, the human sensory bubble is not

intrinsically superior to the others, it is just different as they all are. Again in Yong’s

words, “Animals are not just stand-ins for humans or fodder for brain storming

sessions. They have worth in themselves. We’ll explore their senses to better

understand their lives.”.

For example, we are proud of our excellent colour vision. It used to be almost universally accepted that other animals see the world in black and white. That’s now known to be completely false. Dogs have two base colours – blue and yellow, as opposed to our three – red, green and blue, so their colour spectrum or “rainbow” looks different and less rich than ours. It's two instead of three dimensional. On the other hand, hummingbirds see in the ultraviolet in addition to red, green and blue. So they have a four dimensional colour pallet that may be much more rich and extensive than ours. Bees see ultraviolet too and flowers are much more concerned about attracting their attention than ours. Their pollen areas are often coloured in ultraviolet.

|

| Zebra at night WE can see stripes but... |

We all know

that mosquitos smell animals by picking up carbon dioxide. I didn’t know that

they could smell through their feet. As a result, when they land on exposed

skin, they can pick up a delicious skin smell. But if there is some DEET on the

skin, they immediately take off again in the same way that we'd jerk our hand away from a hot object without conscious volition. That is why you have to cover all your

skin. A general spray in the air isn’t going to work.

It's the

understanding of other creatures that flows from the book that I find the most

fascinating. If you wonder about these things as I do, you will be richly

rewarded by An Immense World.

Sounds like a fascinating book, thanks, Michael. And, yes, I DO see the shark. :-) Love stereograms. I remember when they first came out, and how hard it was to get that first one to CLICK. Also, how hilarious it was afterwards, when other people would stare and stare, and then scoff that it was all a fraud. :-)

ReplyDeleteThanks, Everett. There's actually quite interesting science behind stereograms. Definitely not a scam!

ReplyDeleteSounds like my type of book.

ReplyDeleteDammit! I can’t see the shark! Am I defective in some way?

ReplyDeleteROFL! Sorry, couldn't help it. It will help if you click on the picture, to see it "full size", larger on your screen. Then, get your face maybe 9-12" from the screen, staring at the center of the picture. Then, here's the real trick: stop TRYING to see it. Relax, let your eyes de-focus, or rather, RE-focus BEYOND the picture, as if you're looking THROUGH the screen, at something several feet beyond the screen. Then, SLOWLY, focus SLIGHTLY closer, and closer... when you find the proper focal point, you'll start to see shapes forming out of the dots. Stay relaxed at that point, don't try to look AT them. Just slowly play with your focus, moving "in and out," and eventually you'll find the point at which your eyes will LOCK ONTO the image, and you'll see the shark FLOATING in front of the background noise.

DeleteGood luck! It really is quite remarkable when you learn to do and first see it. Then, it's like riding a bike (or maybe having sex): it's always easy from that point on. But the first time, it can be a challenge to figure out. :-)

From AA: Thank you, Michael. Book bought!! Years ago, you introduced us to Apopo, an organization that trains African pouched rats to detect landmines and tuberculosis. My small monthly motivation is still going so, I am kept informed of what my adopted rat is up to. I love this way in which humans have learned to "extend" our information gathering beyond our own senses.

ReplyDeleteThen of course, with human animals there is the ability of some to ignore the information they senses are giving them, and to be senseless instead.