Annamaria on Monday

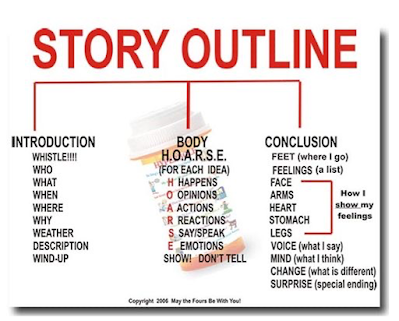

First, some underlying definitions here. In crime writing, there are authors who believe that it is impossible to write a good crime novel without a detailed outline. These sorts of writers are called plotters. Some of them behave like the Jehovah's Witnesses of fiction writing. They loudly insist that no one could write a good crime novel without a detailed and all-powerful outline. They brook no denial of their first commandment. Then there are those of us called pantsers. (To dyed-in-the-wool plotters, the word is a pejorative.) We have an idea of where our story begins and where it is going. We spend a goodly amount of time understanding our characters and getting background information on the situation we are putting them in. Then we write (from the seat of our pants), following the characters into the story and writing down what they do and say. Somehow the arc of the story emerges from the dynamic between the situation and the people in it

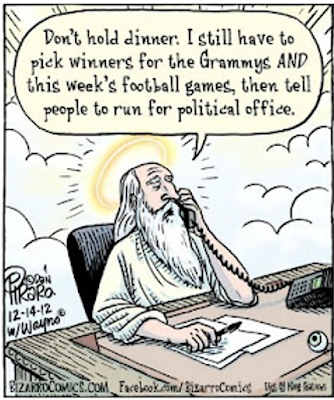

What, you may wonder, does this have to do with the Deity in this blog's title? Well, I was inspired to take up this subject because of a very stimulating discussion that took place last week when I wrote about Originalism in American politics. Two extremely astute regular readers of MIE—Everett and Kathy—commented on that post about the current state of the world. I agreed with everything they said about how things are going, both within the United States and internationally. They painted, as you can imagine, a sometimes-grim picture.

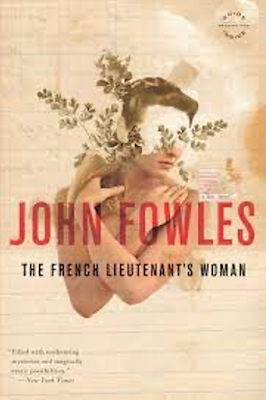

Pondering the state of world and how it got this way brought me to thinking about the best words I have ever read about the relationship between an author of fiction and his or her characters—a comparison of writers’ relationships with their creations and the relationship between the Creator and his (sic) creatures. Here are words quoted from Chapter 13 of the great, the glorious John Fowles’s landmark novel The French Lieutenant’s Woman. Fowles, you will see, was a pantser:

You may think novelists always have fixed plans to which they work, so that the future predicted by Chapter One is always inexorably an actuality of Chapter 13. But novelists write for countless different reasons: for money, for fame, for reviewers, for parents, for friends, for loved ones; For vanity, for pride, for curiosity, for amusement: as skilled furniture makers enjoy making furniture and as drunkards like drinking, as judges like judging... I could fill a book with the reasons, and they would all be true, though not true of all. Only one same reason is shared by all of us: we wish to create worlds as real as, but other than the world that is. Or was. That is why we cannot plan. We know a world is an organism, not a machine. We also know that a genuinely created world must be independent of its creator; a planned world (a world that fully reveals its planning) is a dead world. It is only when our characters and events begin to disobey us that they begin to live...

In other words, to be free myself I must give (my characters) their freedoms as well. There is only one good definition of God: the freedom that allows other freedoms to exist and I must conform to that definition.

Pantsing is, some believe, a difficult way to write a story. It's all too easy, especially in a mystery or thriller, for the author to paint him or herself into a corner. The story can become chaotic, and perhaps not even the author will know where it's going. These problems can put a pantsing author on edge. But this is also a big advantage. It also means that the story is so unpredictable that even the creator of it is filled with suspense.

When I look at the political state of the world at this moment, I see what certainly could be the result of chance, or entropy. Or it could be—in fact I think it is—the collective result of actions of a huge number of creatures endowed with free will. It has all the earmarks of millions of combined stories--tragedies and comedies, romances and thrillers, even literary novels where nothing much seems to happen. We are the characters in these stories. Because of things that happened in previous chapters already written, our lives are filled with difficult decisions, individual problems that sometimes seem unsolvable.

There certainly is a lot of suspense!

And whether there is a God or not, we creatures have to find our own way out of the chaos.

Perhaps because I am a pantser novelist, I do not spend very much time wringing my hands over the state of the world. I think about it, certainly. It breaks by heart. But I do not become depressed or loose my joie de vivre. You see, even in my own stories, my characters have gotten in a bind when it comes to how they are going to get out of the trouble. Every time this has happened, a solution showed up, because one of the characters did something unexpected. And my characters cannot be smarter then I am. And I know that the real world is replete with people a whole lot smarter than me.

I know that I may sound jejune when I say that we will find our way out of this. I do deeply regret that a lot of suffering that has to happen in the meanwhile. But I also know that no good story is about people who are all happy and have no problems to solve.

I agree that to many human beings don't have enough peace and comfort right now. But I also know that things have been a whole lot worse than they are now, and our species survived. I've written here a number of times about factual trends that show how the lot of human beings has improved over the past two and a half centuries.

Our collective self will survive. And we will have great stories to tell when we do!

My job, as I see it, is to be part of the solution. Not part of the problem.

Wonderful!

ReplyDeleteThank you, Elizabeth!

DeleteI completely agree with your final paragraphs, AmA (the ones below the God cartoon). As for plotting vs. pantsing, I'd posit that most creators are a mixture of both: few pansters just write stream-of-consciousness all the way through the story, and even the most dogged plotter must eventually "stream-the-consciousness" of the actual words that go into a paragraph. It's a rainbow spectrum, and each creator is a different color on different days, traipsing back and forth across that brilliant arch.

ReplyDeleteThank you,EvKa. I once moderated a Panser vs plotter panel. One of the plotters insisted that books written without an out were always inferior. I asked him if he ever changed his mind as he was writing. He said, “Of course, but that just normal.” You would have been proud of the way I was able to keep from smirking.

ReplyDeleteAA- I love this and your John Fowles quote ( I love him, we should discuss) has convinced me to change what I'm writing this week and instead talk about a quote from Daniel Martin. Thanks for this!

ReplyDeleteBetween the last paragraph of the Fowles quote and the cartoon, you made my day, Sis. Great seeing you at Bcon. xx J&B

ReplyDelete