Jeff–Saturday

I cannot think of a quicker way to start an argument than with a “Top Ten” anything list. And when you dare to do so in a field peppered with friends whose work undoubtedly deserves mention, you’re guaranteed to find yourself crossed off a lot of holiday greeting card lists.

Yet, as a former adjunct professor of English teaching mystery writing at a college that’s decades older than the modern detective novel, how could I refuse the honor of such a request from the 2023 Mystery Writers of America Ellery Queen Award winning The Strand Magazine? Though, I must admit to prayerfully falling back upon my one-time lawyerly skills to ameliorate the potential fallout by offering up, in roughly chronological order, this ten best list of seminal short stories penned by writers no longer with us.

So here's my article as published by The Strand Magazine, courtesy of the online posting skills of Talia Tydall.

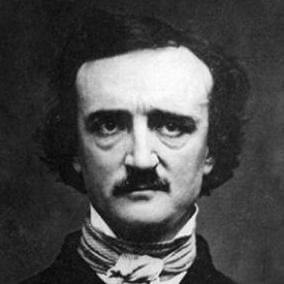

“Murders in the Rue Morgue,” by Edgar Allan Poe (Graham’s Magazine, 1841)

It’s only appropriate that the first story on my list is considered the first modern detective story. In Poe’s tale, he introduces his brilliantly analytical detective, C. Auguste Dupin, and Dupin’s trusted friend who acts as the story’s narrator. Their relationship and Dupin’s methods and cool demeanor have come to serve as inspiration for legions of mystery writers,

It’s only appropriate that the first story on my list is considered the first modern detective story. In Poe’s tale, he introduces his brilliantly analytical detective, C. Auguste Dupin, and Dupin’s trusted friend who acts as the story’s narrator. Their relationship and Dupin’s methods and cool demeanor have come to serve as inspiration for legions of mystery writers,

On Paris’ Rue Morgue at 3AM, a mother and daughter are brutally and inhumanely slaughtered in their heavily locked-down fourth-floor apartment. Neighbors heard their shrieks but also two additional voices coming from within the apartment, one identified as male and French, the other as shrill and foreign. When the neighbors break into the apartment, they find only the daughter inside, dead and stuffed feet-first up the chimney in a show of superhuman strength, while her mother lay decapitated on the ground, four unscalable stories below a still locked window. Though newspapers call it an impossible crime to solve, and the police remain baffled, a man known to Dupin is accused of the murders. Through the application of his “ratiocination” investigatory methods that do not ask “what has occurred,” but rather, “what has occurred that has never occurred before,” Dupin determines what transpired and frees an innocent man; establishing in the process an enduring classic formula for mystery writing.

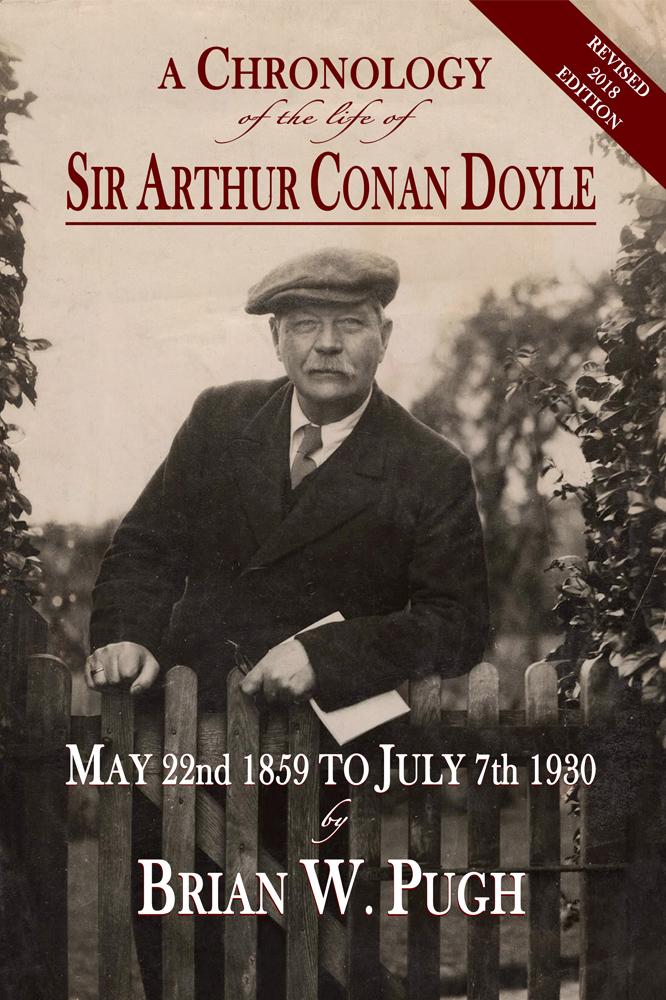

“The Red-Headed League,” by Arthur Conan Doyle (The Strand Magazine, 1891)

I trace my interest in writing mysteries to my early years as a lawyer when I found an unexpected opportunity to read The Complete Sherlock Holmes straight through from cover to cover. By the end of that exercise, I was thinking like Holmes, loving Conan Doyle’s beautiful Victorian prose, and enthralled at the thought that since Sherlock’s father’s first name is “Siger” we were related…if not as kin, at least as kindred spirits. From the perpetual flow of new Sherlock Holmes-themed projects coming to market, I’d call him a true cultural phenomenon.

I trace my interest in writing mysteries to my early years as a lawyer when I found an unexpected opportunity to read The Complete Sherlock Holmes straight through from cover to cover. By the end of that exercise, I was thinking like Holmes, loving Conan Doyle’s beautiful Victorian prose, and enthralled at the thought that since Sherlock’s father’s first name is “Siger” we were related…if not as kin, at least as kindred spirits. From the perpetual flow of new Sherlock Holmes-themed projects coming to market, I’d call him a true cultural phenomenon.

It’s hard to pick a favorite Holmes story. In “The Red-Headed League,” experts see themes of man-to-man confrontation and greed, plus Holmes’ high opinion of himself and distain for lesser minds. To me, there’s an added lesson: know your setting well, because from that knowledge you may find your answer. The assistant to a red-headed pawnbroker shows his boss an ad offering a busy-work office job paying male red-heads exorbitant wages and convinces him to take the job. Eight weeks later the pawnbroker finds the office suddenly closed and that the landlord never heard of the League, He turns to Holmes, who visits the pawnshop with Watson and concludes he knows the answer to the mystery. Conan Doyle considered this story his second favorite. “The Speckled Band” was his first.

“Locked Doors,” by Mary Roberts Rinehart (1914)

Born in my hometown of Pittsburgh in 1876, she is buried at Arlington National Cemetery and identified there as: “America’s first woman war correspondent during World War I for the Saturday Evening Post; wrote mystery novels, including The Circular Staircase and The Bat; in 1921 was referred to as ‘America’s Mistress of Mystery.” A fearless woman, also called “America’s Agatha Christie,” she’s credited as the inventor of the “Had-I-But-Known” mystery novel, and for the phrase “the butler did it.” Her best-selling books and plays were often adapted for film and one novel was among the earliest “talking book” recordings.

In much of Rinehart’s work the challenge is discovering what’s hidden from view, because the “hidden situation” looms more important than whodunit. An accomplished mystery writer trained in nursing, Rinehart combined those talents in her series featuring nurse Hilda Adams a/k/a Miss Pinkerton, who at times works undercover for the police. In “Locked Doors,” she’s recruited to replace a badly shaken nurse who came to the police after four days of living in a large eerie house, working for a peculiar family with no servants, no working telephone, two young children confined to their room, and doors barred shut at night. Its spine chilling, not-your-normal-mystery sort of “Gothic thrills” plotting, might just keep you from guessing the “perfectly macabre solution to this mystery.”

“The Adventure of the Egyptian Tomb,” Agatha Christie (The Sketch Magazine, 1923)

What more can I possibly tell you than you already know about Dame Agatha Christie, the undisputed Queen of Crime and creator of Hercule Poirot, Miss Marple, and the world’s longest running play, “Mousetrap.” Hmm, perhaps you didn’t know that this best-selling fiction writer of all time with more than two billion novels sold (trailing only the Bible and the works of William Shakespeare) loved surfing? That was news to me, so I took it as a suggestion on how to find a favorite among her more than 150 short stories. I went surfing through her work and came up with this Poirot and Captain Hastings gem that’s celebrating its one-hundredth anniversary.

The widow of a famous Egyptologist asks Poirot to journey to the excavation site of a Pharaoh’s tomb where her husband died by heart attack, the wealthy backer of the dig died from blood poisoning, and from which the backer’s nephew left for New York only to commit suicide soon after arriving there. The widow fears for the life of her son who intends on continuing his father’s work. Poirot cables New York for information on the nephew, and leaves for the dig. By the time he and Hastings arrive, another American has died, this one from tetanus, and talk of an Egyptian Curse fills the papers. Tension builds as Poirot suddenly begins choking on tea he’s been served. It’s a tour de force example of how Christie’s least likely characters so often turn out to be the guilty, and of Poirot’s penchant for gathering the guilty together for their unmasking.

“Blackmailers Don’t Shoot,” by Raymond Chandler (Black Mask, 1933)

Chandler is considered a founder of the hard-boiled school of detective fiction. Mention his name and private detective Philip Marlowe immediately springs to mind. Chandler coined the phrase “down these mean streets” and Marlowe lives on them. It’s a rough place for a compassionate guy with a more noble sense of purpose than accumulating wealth and power. Marlowe’s compassion makes him vulnerable, and so he plays a tough guy to the world, using wise cracks as his defense to whatever that world throws at him.

Chandler is considered a founder of the hard-boiled school of detective fiction. Mention his name and private detective Philip Marlowe immediately springs to mind. Chandler coined the phrase “down these mean streets” and Marlowe lives on them. It’s a rough place for a compassionate guy with a more noble sense of purpose than accumulating wealth and power. Marlowe’s compassion makes him vulnerable, and so he plays a tough guy to the world, using wise cracks as his defense to whatever that world throws at him.

“Blackmailers Don’t Shoot” is Chandler’s first mystery story, written when he was 44. Αll the dames, guns, gangsters, shady dealings, lies, deceptions, crooked cops, fights, tough guy talk, and elements of the mythical quests knight Marlowe feels compelled to pursue are there. But not yet the Marlowe name. That change doesn’t happen until 1939 in “The Big Sleep.” In 1933 he’s Mallory and at center stage in a swanky club attempting to blackmail a beautiful movie star over love letters she’d long ago sent to a gangster. She dismisses the attempt, leaves the club, and is kidnapped. Mallory leaves later, only to be strong-armed into the middle of a falling out among gangsters over her kidnapping. He turns the situation to his advantage, leading to the Star’s ultimate rescue, the death of her gangster ex-boyfriend, and the return of her letters. But Mallory has more left to do. Chandler likes it that way.

“Death Threats,” by Georges Simenon (cir. 1936-42)

SIMENON, Georges, 1963, Ecrivain (F) © ERLING MANDELMANN ©

Belgian writer Georges Simenon is one of the most prolific authors of the 20th Century, estimated to have written over 400 novels, plus as many as 1200 stories under his own name and more than a dozen pen names. His sales total more than 500 million copies, and his highly popular Inspector Jules Maigret appears in 78 novels and 28 short stories, often confronting serious themes rarely touched upon by more traditional detectives. Maigret does not adhere to the genre’s conventional approach of searching for clues and using deductive reasoning to solve a case. Rather, he immerses himself in the surroundings and life of those who interest him, much as would a therapist or professor looking for psychological insights to help better understand the human condition and criminal mind.

“Death Threats” has Maigret dispatched to spend the weekend at the country villa of the senior member of a wealthy merchant family. The merchant received an anonymous note threatening his death before 6PM on Sunday. His twin brother reaches out to Maigret trying to convince him that his brother is paranoid and the threat must be a joke. At the villa, Maigret discovers a family of ambitious, self-absorbed, greedy narcissists wracked by mutual hatred for each other, who despite all their advantages, utterly fail to appreciate life. Things get exciting around 6, but don’t go quite as Maigret had expected even though he knew from the outset who’d sent the note.

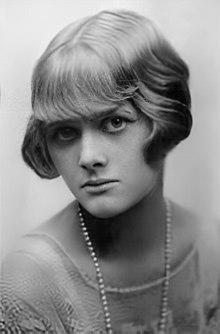

“Kiss Me Again, Stranger,” by Daphne du Maurier (Gollancz, 1952)

Du Maurier’s work rarely has a happy ending, yet she’s often described as a romantic novelist, a characterization she rejected and despised. Fantasy and mystery were descriptions she might have found more to her liking. Whatever one’s opinion on that debate, her short stories are certainly dark, if not noir, hovering close to the paranormal and often haunting the reader long after the final sentence is read.

Du Maurier’s work rarely has a happy ending, yet she’s often described as a romantic novelist, a characterization she rejected and despised. Fantasy and mystery were descriptions she might have found more to her liking. Whatever one’s opinion on that debate, her short stories are certainly dark, if not noir, hovering close to the paranormal and often haunting the reader long after the final sentence is read.

“Kiss Me Again, Stranger” is neither a ghost story nor a supernatural tale, but rather a classic example of du Maurier’s uncanny ability to keep the reader thinking it just might end up being one of those. A nameless young man narrates the story of his evening at the cinema where he’s irresistibly taken by a beautiful usherette. He follows her onto a bus, sits beside her, pulls her close to him, and rests her head on his shoulder. I shall not tell you what happens when they later go off together into a cemetery, except to quote what another has written about the usherette: “it is hard to think of any female character in British fiction, before this husky siren, who does what she does and with such cool aplomb: an unexpectedly powerful proto-feminist role model.”

“The Oblong Room,” by Edward D. Hoch (The Saint Magazine, 1967)

Edward Hoch is the author of close to 1000 classic detective stories, a record holder with Ellery Queen’s Mystery Magazine for having published a short story in every one of its issues over a thirty-four-year span, and the first short story writer to be named a “Grand Master” by Mystery Writers of America. His work emphasizes mystery and deduction over other forms, but seldom are they simple police procedurals, and at times they’re locked rooms and impossible crimes scenarios. His small town, Connecticut police Captain Jules Leopold has weathered close to fifty-years and one hundred stories, including the Edgar award winning, “The Oblong Room” – an homage of sorts to Poe’s “The Oblong Box.”

In “The Oblong Room,” Captain Leopold is called to investigate what seems an open and shut case of murder on a college campus. A man is found stabbed to death, locked in a room for 24 hours with his roommate. All that is needed to convict is the roommate’s motive, but the roommate will not make a statement. The ensuing investigation establishes, (a) the victim possessed an uncanny ability to manipulate anyone into obeying him, (b) no one was more devoted to and protective of the victim than his roommate, and (c) the two were known to use LSD. But why did the roommate kill someone he’d die to protect? And why a 24-hour vigil after the slaying? Our answers arrive in a do-not-see-it-coming solution.

“The Last Bottle in the World,” by Stanley Ellin (Ellery Queen’s Mystery Magazine 1968)

This three-time Edgar award winner and Mystery Writers of America Grand Master is said to have focused so intently on perfection that it would take him a year to complete each short story he submitted to Ellery Queen’s Mystery Magazine. His ingenious imagination, precision plotting, strong characters, chosen locales, and deft ability to fool and surprise the reader from a psychological point of view, all served to focus attention on his protagonist’s crisis at hand.

This three-time Edgar award winner and Mystery Writers of America Grand Master is said to have focused so intently on perfection that it would take him a year to complete each short story he submitted to Ellery Queen’s Mystery Magazine. His ingenious imagination, precision plotting, strong characters, chosen locales, and deft ability to fool and surprise the reader from a psychological point of view, all served to focus attention on his protagonist’s crisis at hand.

In this story about the last bottle of a famed vintage that a mega-rich man is determined to buy from the narrator-wine merchant, the merchant unexpectedly comes across the rich man’s wife in a café, and there’s a flashback to when the two first met. She’s now in a difficult marriage and showing interest in another man. The tension rises, until the plot unexpectedly twists in a most satisfying yet realistic of ways.

“Blood Lines,” by Ruth Rendell (Hutchinson (UK), Crown (US), 1995)

Writing also as Barbara Vine, Ruth Rendell is a literary giant of the 20th Century, possessing an uncanny knack for weaving the strangest of tales out of the joys and pains of ordinary family life. Rendell offers up her themes on multiple penetrating levels, drawing upon ancient tragedy, quixotic dark humor, poignant intellect, and piercing insights into the darkest regions of the human psyche to reveal the disturbed family relationships unearthed in her works. In the process, often shocking the reader at how fragile the separation between life on the page and off.

Writing also as Barbara Vine, Ruth Rendell is a literary giant of the 20th Century, possessing an uncanny knack for weaving the strangest of tales out of the joys and pains of ordinary family life. Rendell offers up her themes on multiple penetrating levels, drawing upon ancient tragedy, quixotic dark humor, poignant intellect, and piercing insights into the darkest regions of the human psyche to reveal the disturbed family relationships unearthed in her works. In the process, often shocking the reader at how fragile the separation between life on the page and off.

“Blood Lines” features her popular Inspector Reginald “Rex” Wexford investigating a murder that’s shattered the tranquility of a small bucolic community. A young woman discovers her stepfather’s brutally beaten body. She firmly denies knowing the identity of the murderer, but Wexford is convinced his primary suspects include the victim’s extended family. Wexford’s patient investigation reveals evidence of spousal abuse, infidelity, avarice, and betrayal, reminding him that the criminal impulse may be present in even the most routine or intimate of situations. It is vintage Rendell.

© 2023 Jeffrey Siger

JEFFREY SIGER fled his career as a name partner in his own New York City law firm to live and write mystery thrillers on the Greek island of Mykonos. The New York Times picked him as Greece’s thriller novelist of record, and Reader’s Digest Select Editions described him as one of its “new favorite authors.” He’s received Lefty and Barry “Best Novel” nominations, been Chair of Bouchercon, and served as adjunct professor of English at Washington & Jefferson College teaching mystery writing. Jeff blogs Saturdays on murderiseverywhere.blogspot.com and the 13th book in his Chief Inspector Andreas Kaldis series will be published by SEVERN HOUSE in February 2024. Visit him at www.jeffreysiger.com

--Jeff

Thanks for such an amazing list, Jeff. My TBR pile has swelled again, I fear. Some of these I have read, but others are new to me, and I can't wait to dive in and discover them. Your recommendations carry weight with me. Zxx

ReplyDeleteI'm flattered beyond words, Zoë, thank you. And yes, I miss your presence already. xx

DeleteHow very clever of you, Jeff, to do it this way. There are four of these I've yet to read, but I will remedy that as soon as possible. Great post.

ReplyDeleteThanks, Wendall. The most challenging part of the piece was figuring out how to best avoid a lynching. :)

DeleteYou not only write mystery thrillers on Mykonos, but you live mystery thrillers on Mykonos, too??? Wow, WHAT a life!

ReplyDeleteGREAT article, Jeff, loved it.

Thanks, EvKa, for grasping the essence of my hard life on the Greek isles...and your most flattering and welcome compliment on the article.

DeleteThank you for this Jeff! There's four here I haven't read (wonder if they're the same 4 as Wendall's!) but I'm going to!

ReplyDeleteThanks, Ovidia! It was a lot of fun preparing the piece, but admittedly intense considering the many potential alternative views.

DeleteReally enjoying the re-reading you've spurred me on to too! Can imagine how intense the process was--I'm guessing you had to re-read three to five times what you listed here? (Maybe share a list of your runner-ups some time...)

DeleteThanks again, Ovidia. The only way I found the necessary concentrated time was when I was stuck in bed for a week with a horrid stomach virus. The research distracted me from my condition. If a runners-up list requires anywhere near the same sort of "motivation," I'm not looking forward to heading down that road anytime soon. :)

DeleteI guess we all have our own muse. Yours are just far more numerous and far smaller than those for the rest of us (I hope...)

DeleteI feel as if I'm about to be graded by a master, Michael. :)

ReplyDelete