This past week, a writer friend told me that he has, in his future, a meeting with a person who is researching "railroads in East Africa!" He asked me if one of my books takes place against the building of the railway. But that all happened about seventeen years before my stories start. The railway is, however, an essential part in most of my stories. My characters travel by train, beginning with the first book in the series: Strange Gods, just now out in a new edition.

Since the new edition of that book just launched, I took that question as a suggestion for today's blog. Here is repost of my blog about the creation of what came to be known as "The Lunatic Express."

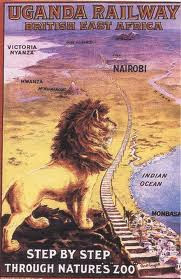

It was called the Uganda Railway, but all of it was in the Protectorate of British East Africa, now Kenya. It goes 660 miles from the port city of Mombasa, on the Indian Ocean, to Kisumu on the Eastern shores of Lake Victoria, across the water from Uganda.

It is credited with cementing Britain’s colonial power in

East Africa.

But also with being instrumental in stopping the “trail of

tears”—the route where slaves were dragged from the interior to the coast and

then shipped to work in the households of Asia Minor and on the sesame plantations

of the Zanzibar.

Construction began in 1896. It cost Great Britain’s taxpayers 55 million pounds

sterling: £20.1 Billion or $33 Billion in today’s money.

If the indigenous people tried to stop its progress through

their territory, “punitive expeditions” were sent out to put them in their

place. Keep in mind that the King's African Rifles had firearms. The tribal

people fought with iron (not even steel) spears and swords. Still, the Maasai won one of those battles.

Its engineers and construction crews braved man-eating lions

and deadly scorpions.

2,498 perished during its construction.

Before the Brits built the railroad, the route from Mombasa

to Kisumu was an oxcart trail. To

traverse from the coast took about three months with most of the party

walking, carrying water and food. Ordinarily

around three hundred at a time, most of them tribal porters, made the trip. People died.

A new way to travel that distance was called for. But not everyone agreed.

A new way to travel that distance was called for. But not everyone agreed.

Calling the railroad a “gigantic folly,” Liberals in Parliament were

against the project, saying that Britain had no right to drive what African’s

called the “Iron Snake” through Maasai territory. The magazine Punch called it “the Lunatic Line.”

In 1971, Charles Miller wrote a book about it: The Lunatic Express: An Entertainment in Imperialism. Many politicians and newspaper editors

called it a waste of the taxpayer’s money.

Shaky wooden trestles over enormous chasms, hostile tribes, workers dying

of until-then unknown diseases—much of what transpired seemed to support those

against the idea.

But from the outset, the Uganda Railroad had its adherents. Conservatives saw it as an important salvo in

the “Scramble for Africa,” that Nineteenth Century madness of the European

powers to take over whatever chunks of the African continent they could lay

their hegemony on. Winston Churchill

admired it as “a brilliant conception." He said, “The British art of ‘muddling through’ is seen here in one of

its finest expositions. Through

everything—through forests, through the ravines, through troops of marauding

lions, through famine, through war, through five years of excoriating

Parliamentary debate, muddled and marched the railway.”

In the end it was seen as a huge achievement—both strategically and economically. It became vital to the suppression of slavery. Its existence eliminated the need for huge squads of human beings to carry goods.

The American President Teddy Roosevelt rode the railroad during his visit to British East Africa in 1909. He wrote, "The railroad, the embodiment of the eager, masterful, materialistic civilization of today, was pushed through a region in which nature, both as regards wild man and beast, does not differ materially from what was in Europe during the late Pleistocene." On his way into the interior from the coast, he often rode on a platform on the front of the locomotive, giving him a great vantage point for viewing the huge array of wildlife along the way. According to Teddy, "...on this, except at mealtime, I spent most of the hours of daylight." It's a view I sorely wish I could have seen.

Here is a link to give you a glimpse of the line as it passes

through some of the most incredible scenery on earth, as shown in the opening

credits of Sydney Pollack’s brilliant Out

of Africa.

htttp://www.youtube.com/watch?v=9FB1LS3WhIU

htttp://www.youtube.com/watch?v=9FB1LS3WhIU

So many eras we'd love to be able to time travel and see... minus the disease and mortal danger involved, of course. Thanks, Annamaria!

ReplyDeleteE, I once heard Ann Perry give a speech in which she said that historical novelists provide time machines for people to witness history safely. I don't have her better words but the gist of it was that we can make readers feel they are there in the trenches of the Somme or the fall of Rome, with the risk of shrapnel or starvation. As one who tries mightily to reach such vivid portrayals, I have no illusions about actually wishing I had lived in the past. MY essentials for any century I would want to inhabit are hot showers, underarm deodorant, antibiotics, and painless dentistry.

DeleteOnce again TR is at the front of recognizing the balance between progress and environmentalism....btw is that a rife between his legs (no Mae West lines please).

ReplyDeleteListen, Big Boy, before you go shooting off your mouth about TR, you ought to know that common practice at the time he rode the railroad was to shoot game from the train. Besides, suppose they had to make a stop and one of the man-eating lions of Tsavo was lurking near the tracks.

DeleteThank you for this. It made somethings clearer about the movie, and wonderful, realistic word pictures of Kenya.

ReplyDeleteThank you, Lil. More on this subject to come next week. The time and the place are endlessly fascinating to me. Enough conflict among the groups and within the groups there and then to keep this mystery writer occupied for a long time.

DeleteOh, how I long for a Teddy Roosevelt today!!!!! Thelma Straw in Manhattan

ReplyDeleteThelma, Teddy was 51 when he went to British East Africa in 1909 and he had already been President of the United States.

ReplyDeleteLove, love, love this, thanks so much for posting.

ReplyDeleteBrilliantly presented! Your post is both insightful and thought-provoking. Appreciate you sharing your valuable perspective. Join the Aviator community on our blog platform.

ReplyDelete