Russia’s invasion of Ukraine is sending ripples of pain from the traumatically besieged country to the rest of the world. I fear for the trapped Ukrainians and foreigners unable to escape the Russian military. I marvel at the resistance of Ukrainians who are literally giving their lives for their country's independence.

What can I do? is a question a lot of us in the West are asking.

Some people dress in yellow and blue, and others sew Ukrainian flags to hang from their homes. Bartenders stop pouring Stony. People who have dealings with Russia, including authors and literary agents, are pondering whether these ties should also be severed.

Shortly before the invasion, I signed a book publishing contract with an independent Russian publisher (an organization that is not supported by or affiliated with the government). I realize this pending sale is far more than a financial transaction.

Ukraine’s chapter of PEN, a nongovernmental organization devoted to protecting freedom of speech and authors’ rights, called for a global boycott of books by Russians. They also advised authors and agents to stop selling rights to Russia. This year’s Frankfurt Book Fair in Germany, and the Bologna Children’s Book Fair in Italy, decided to exclude Russian publishers and agents. Stephen King and Linwood Barclay, American-born authors who are bestsellers worldwide, both said they won’t renew existing contracts to publishers in Russia.

Avoiding publication in Russia is every writer’s choice—just as it is to publish or not in any country, including the United States, Israel, and other controversial countries. Yet I am concerned by the quick dismissal of the importance of foreign books in Russia. Novels, nonfiction, memoirs, poetry and graphic novels teach us about the unfamiliar. Books support us when we’re isolated, and they can sometimes even inspire us to change our lives.

Another consideration is whether the people working in Russian publishing are actually in solidarity with Ukraine. Several hundred publishing professionals inside Russia have spoken out against the invasion in a powerful letter of protest. Some of the independent publishers have been arrested. Their bravery is a huge contrast from the silenced publishing world of the Soviet era.

|

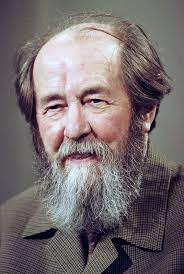

| Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn, courtesy Brittanica |

During my childhood, the Russian dissident author Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn couldn't be published in his own country, and he emerged as one of the world's most popular cultural heroes. I remember hearing that he won the Nobel Peace Prize in 1970. I was shocked that an author of a book somebody disliked could be sent to a forced labor colony.

|

| Vasily Aksyonov, courtesy Brittanica |

In the 1980s, a lauded novelist named Vasily Aksyonov was allowed to leave the Soviet Union after years of censorship and imprisonment. Aksyonov spent 24 years in the US, and among his many professorships was one teaching at Johns Hopkins University. My husband was in his class and remembers Aksyonov explaining how a small group of Russians typed copies of his banned books. He stressed the scarcity of copies in the country—less than fifty existed—and how these packaged papers were secretly passed between people, each hoping the next wasn’t a spy who would turn them in.

After the U.S.S.R. was dismantled into independent countries, both writers returned to Moscow, where they died as elderly men of natural causes.

I bring up these Russian writers because, although I support sanctions against big Russian players like oil, airlines and banks, I am concerned about taking away books; and also the plight of Russian war resisters. I'm picturing Russian citizens who feel as endangered and powerless today as their parents and grandparents did. Yet despite the risks, political protests are roiling the streets of Russia. On Sunday, March 6, 4500 protesters were arrested. Even children as young as five years old have been taken from public protests to jail. I expect bloodshed at forthcoming protests in Russia, just as blood is flowing in Ukraine.

The history of Soviet censorship can be compared with the acts of other governments. My historical novels explore the history of a subjugated colony whose people have a seemingly impossible-to-reach goal of ruling themselves. In The Widows of Malabar Hill, The Satapur Moonstone and The Bombay Prince, women protect each other and gather strength to fight power during India’s very difficult period of protestor suppression by its non-elected, foreign government.

Now that Russia is at war, and its citizens back home are restless, would the Kremlin censor such books?

Possibly.

And that’s why I'm not doing the job for them.

One thing I do not think is fair is to ban Russian artists, musicians, singers, athletes, actors, writers, or to vilify them or bkame them for anything. And even Russian cats are vilified! I mean, really?

ReplyDeleteOne thing that's important that I've heard from a friend who reads about six languages and many European newspapers and communicates with several Europeans is that they are terrified of a nuclear war happening. And if it happened, whole countries could be wiped out.

That is what I worry about overall, the potential for that happening.

I agree with you, Sujata. I think that censoring non-government publications from, and international publications to, Russia merely help the regime there. Whether you will ever get paid is another question, of course...

ReplyDeleteI've been asked to participate in a conference in Greece on the subject of burgeoning calls for censorship in the West, particularly the US. It should be an interesting back and forth and back and forth and....

ReplyDeleteIt troubles me that the Russian people will be universally vilified for the actions of the egomaniac who is running their country. I know from a Russian friend how dangerous it is for common people to speak out there.

ReplyDelete