I am writing this about my father on Sunday, June 16th - Father's Day in the USA.

Summing up Sam’s life is difficult, because he ranged so far and so deep for so long. Sam was an extraordinary person masquerading as everyman. He was modest and thought little of his gifts. But they were huge.

He was an eyewitness to many of the historic events of his century. And he had the wisdom and sensitivity to see them for what they were.

He was born on the 5th of March 1914 to Andrea Puglisi and Concetta Bruno in a coal mining village - Holsopple - in Western Pennsylvania. His father was a miner. His mother bore six children, kept a cow and chickens, raised vegetables, and was required to keep house for five other Italian-speaking coal miners in exchange for the privilege of living with her husband and children in mine-owned housing. Sam was baptized Salvatore Francesco Puglisi the following September. The spelling of his family name had been changed on US official records by some immigration clerk's failure to dot the final i when his father came through Ellis Island.

He was born on the 5th of March 1914 to Andrea Puglisi and Concetta Bruno in a coal mining village - Holsopple - in Western Pennsylvania. His father was a miner. His mother bore six children, kept a cow and chickens, raised vegetables, and was required to keep house for five other Italian-speaking coal miners in exchange for the privilege of living with her husband and children in mine-owned housing. Sam was baptized Salvatore Francesco Puglisi the following September. The spelling of his family name had been changed on US official records by some immigration clerk's failure to dot the final i when his father came through Ellis Island.

Sam's earliest memory was of the influenza epidemic of 1917 and 18: of standing in the doorway watching his mother who lay on the bedstead with her own infant cradled between her knees while she nursed two other babies who had lost their mothers in that plague. When Sam—who must have been only three or four years old at the time—described the tears running down his beloved mother’s cheeks, you felt you could see them too.

When he was six or seven, he hid in that bedroom with his mother and his siblings, while his father sat guard outside the door with his hunting rifle and a shotgun across his lap. Outside the window, on the hills, the Ku Klux Klan were burning crosses, threatening the immigrants, the Catholics who worked in the mine, and their families.

Little Salvatore became Samuel Frank when he went to school. His teacher told him she was giving him a real American name, that the name his parents had given him was not American enough. In his adult life, everyone, even his children, called him Sam.

When he was six or seven, he hid in that bedroom with his mother and his siblings, while his father sat guard outside the door with his hunting rifle and a shotgun across his lap. Outside the window, on the hills, the Ku Klux Klan were burning crosses, threatening the immigrants, the Catholics who worked in the mine, and their families.

Little Salvatore became Samuel Frank when he went to school. His teacher told him she was giving him a real American name, that the name his parents had given him was not American enough. In his adult life, everyone, even his children, called him Sam.

He became intrigued when early flying machines appeared in the sky, and he tried to make an airplane of his own. His flight began at the edge of a cliff and landed in a hawthorn tree, and his first adventure in flying ended with a spanking. He also saw planes overhead in the Pacific battles of World War II. And he even had a connection with space flight: he was so proud to have worked on the components of the Apollo Spacecraft.

Concetta moved the family to Paterson, New Jersey, where there was a group of people from her village on the outskirts of Siracusa in Sicily. Sam’s oldest brother Paul, aged 14, went to work in the silk mills and took over support of the family. Sam never went back to school until after WWII.

When he was nine, his beloved father died. Coal miners don’t live long. The mining company put Concetta and her six children, ranging in age from 2 to 14, and her meager belongings on a wagon and drove them to the edge of the “town,” which was in the middle of a woods. They left her there.

Concetta moved the family to Paterson, New Jersey, where there was a group of people from her village on the outskirts of Siracusa in Sicily. Sam’s oldest brother Paul, aged 14, went to work in the silk mills and took over support of the family. Sam never went back to school until after WWII.

Though the Great Depression and the early death of his coal miner father robbed Sam of any chance at education, it also sent him as a CCC youth to the Idaho wilderness.

At the end of that grievous decade, he fell in love with and married Annamaria Pisacane. They both looked like movie stars.

World War II was a central experience of Sam’s life. He fought in the Pacific, and described the battle for Okinawa as hellish. After fighting in many major battles, while others were on their way home, he was detailed to become a China Marine.

After V-J Day, part of the negotiations between the USA and Japan was a deal that the Japanese in China would surrender, not to the Chinese, but to the Americans. (Japanese treatment the of Chinese had been so brutal that the Japanese feared putting their 700,000 men still in China at risk of retaliation.) Sam was one of 3000 American Marines of the First and Sixth Divisions sent to keep the Japanese prisoners of war safe until they could be returned home.

Sam described to me his time there. When the Marines first arrived in Tsingtao, the Japanese were being held in huge barbed wire enclosures. With so many inmates and too few guards, understandably enraged Chinese were slipping under the wires in the night to take their revenge with knives. The American officers in charge decided to increase the guard power by rearming the Japanese officers and having them join the guard patrols. My dad described as otherworldly the experience of walking guard duty with officers who, two weeks before, had been trying kill him.

Sam remained in China for six months and finally returned home in March of 1946, with souvenirs ofChina

|

Sam in Northern Idaho at a CCC Camp in 1933

with a group building infrastructure still in use

in a United States National Park.

|

World War II was a central experience of Sam’s life. He fought in the Pacific, and described the battle for Okinawa as hellish. After fighting in many major battles, while others were on their way home, he was detailed to become a China Marine.

After V-J Day, part of the negotiations between the USA and Japan was a deal that the Japanese in China would surrender, not to the Chinese, but to the Americans. (Japanese treatment the of Chinese had been so brutal that the Japanese feared putting their 700,000 men still in China at risk of retaliation.) Sam was one of 3000 American Marines of the First and Sixth Divisions sent to keep the Japanese prisoners of war safe until they could be returned home.

Sam described to me his time there. When the Marines first arrived in Tsingtao, the Japanese were being held in huge barbed wire enclosures. With so many inmates and too few guards, understandably enraged Chinese were slipping under the wires in the night to take their revenge with knives. The American officers in charge decided to increase the guard power by rearming the Japanese officers and having them join the guard patrols. My dad described as otherworldly the experience of walking guard duty with officers who, two weeks before, had been trying kill him.

Sam remained in China for six months and finally returned home in March of 1946, with souvenirs of

He taught me too many things to enumerate. To love and desire education. Though his father’s untimely death put an end to his formal schooling when he was only nine years old, Sam read and studied all his life—got his GED and took some courses at Rutgers on the GI bill, even while he worked two jobs to keep his family. He read Freud, he told me, because he wanted to understand people and Plato and Aristotle and Schopenhauer because he wanted to understand life.

He was the least judgmental person I ever met—finding the good in everyone, even people who harshly misjudged him and mistook his charity and gentleness for weakness.

He was beautiful, movie star handsome, yet never vain. What was important to him was who and what he loved.

He loved his father and described himself dogging his footsteps and trying to emulate his father’s industriousness, sense of adventure, and loyalty. All virtues he himself achieved, but never bragged about.

He loved music and dancing. He loved to play cards and golf.

He loved the out of doors, especially fishing and left me with vivid memories of following him on sunny spring days, wading in sparkling trout streams and one particularly delicious dinner of fresh-caught trout and sautéed early dandelions gathered on the banks of pristine water.

|

| Sam and me at my 50th birthday celebration |

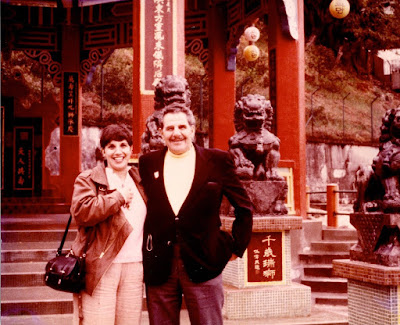

In 1986, as soon as it was possible to visit, David and I took Sam back to China for a three week tour. He was pleased with what he saw. The China he had experienced had been filled with starving, down-trodden, sick people. The China we saw together was on the cusp of becoming the modern power it is now. My favorite memory: An evening in the Rathskeller at the Peace Hotel in Shanghai, when Sam and I danced the polka to the music of six old guys in Mao uniforms playing from sheet music from 1946.

Mostly Sam loved his family and took a Sicilian man’s joy in the fact that his family was united. He always asked, “Have you talked to your brothers? How are Kerry Ann and Ted and the children? Give everyone my love.” He always in every way gave us all his love.

Sam’s life was long, but more important his love was deep and true.

He said he only regretted one thing—smoking cigarettes. He died of complications of emphysema at the age of 94.

He still looked like a movie star.

Lovely!

ReplyDeleteSam was bigger than life to me. He was a wonderful man and I will always remember how loving and kind he was to me when I married Andy.

ReplyDeleteHe loved you, Trish, and was so happy to have a wonderful person like you in our family. He did the same with David. Treated him like a fourth son. He was the father David deserved and had never had before.

DeleteThat would describe him, Stan. And as I am sure I have bragged to you, between the ages of 74 and 85, he shot his age in golf. He complained bitterly to me, when at 86, he kept missing doing it by two or three strokes.

ReplyDeleteWhat a beautiful tribute, sis. I only wish I'd had the chance to meet the man who made you who you are today. And, yes, I'd only say nice things. :)

ReplyDeleteWhat a wonderful story and father, so much to remember and be proud of. And I remember he taught you and your siblings to despise war. Very interesting about an Italian coal miner's family in Western Pennsylvania and your father's life, especially during and after the war.

ReplyDelete