In April, 1974, when a group of thoroughly fed up

Portuguese officers toppled their dictatorship, the shock was felt in several

parts of the world but mostly in Southern Africa where it precipitated massive

change.

Right after their coup, the junta of Portuguese generals

grandly promised “democratic self-determination through negotiation and

consultation” with all in their former colonies.

There followed a long hiatus. Internecine fighting

erupted in Angola. In Mozambique nothing happened. Everybody waited tensely.

Then five months later, out of the blue, the generals

unilaterally announced that the Frelimo movement – their former enemies - were

the rightful rulers of Mozambique. In five days’ time, at midnight on September

7, they would hand over to a transitional Frelimo government and grant full

independence on June 25 the next year.

The turnabout triggered Mozambique’s sad and futile One

Week War.

Wilf

Nussey was a newspaperman for forty years, all but four of them in Africa. He

was the foremost foreign correspondent for the large Argus group of newspapers

for many years spanning most of Africa’s transition to independence and its

continuing upheavals. He was right in

the heart of the One Week War in Mozambique, and here gives us an amazing eye

witness account of a very murky and dangerous event in Africa’s very dangerous and murky history, illustrated by the actual photographs he and his team took at the time.

Wilf’s

on the spot experiences in Southern Africa and his knowledge of the politics of the time provide the background to his excellent

thriller DARTS OF DECEIT.

THE ONE

WEEK WAR

Part I

Part I

Covering conflicts in Africa is usually a grubby

business in broiling desert or sodden bush trailing after a bunch of

disorganised, unruly soldiery along a vague and fluid front line with the

distinct possibility of getting one’s head shot off. By either side. Unless one

is a member of that fraternity of pseudo-hacks who write their reports from the

gossip gleaned in the hotel bar.

Sometimes we got lucky. As in the One Week War in

Mozambique. Not a war, really, but a localised rebellion. But no less vicious

and bloody than the big ones. And, unusually, it was urban.

In Lourenço Marques (now Maputo) and Beira the

reaction by both pro-Frelimo and anti-Frelimo to the announcement of

independence from Portugal was immediate and dramatic. The pros were mostly

blacks with a fair number of whites, mainly students, and the antis were mostly

whites with a sprinkling of conservative blacks.

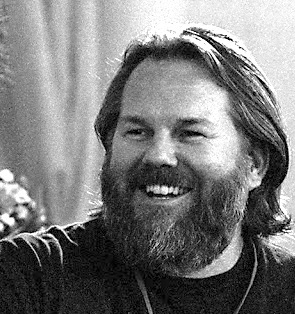

|

A younger Wilf watches

protesting dock workers

|

I and my Argus Africa News Service crew were in the perfect

position to watch the drama unfold. We had an office with a telex in Lourenço

Marques and I always had at least one journalist there, just in case.

Conflict began in September, 1974. It was the

strangest I have experienced: drive a few kilometres to watch confrontation,

bloodshed and destruction; drive back into the lap of five-star luxury with

cocktails, fine wines, gourmet food and rest. Then out again, and so on, and

on.

|

| Rally at Machava stadium |

A big Frelimo rally was scheduled for Friday,

September 6, and I smelt trouble. I flew to join my staffer, Tom, taking with

me Ruphin, a long-haired, bearded Belgian hippy photographer with a flared

Edwardian jacket and a pipe exuding smoke so foul it could drop a fly at forty

paces. We checked into the Polana hotel, the unofficial contact venue for media

and politicians.

Frelimo supporters going to the big Machava stadium on

the outskirts of LM were in no mood to brook interference: a white man with

more bravura than brains got himself beaten to death by blacks when he tried to

stop them.

By mid-afternoon more than 30 000 people were crammed

into it celebrating their imminent independence. They were in a state of high

political intoxication. They sang “Nkosi sikelele iAfrika” and other anthems,

waved flags and banners and displayed huge posters of Samora Machel.

As an exercise in ideological rhetoric at maximum

volume it was peaceful enough: lengthy, boring speeches bellowed through

deafening amplifiers.

We headed back to town and then the trouble began.

It is startling yet stimulating to be in at the birth

of a revolution, to see it bud as a small incident and flower into full-blown

mayhem, like the South American peasant who saw smoke puff from the earth he

was ploughing swell into a towering volcano.

In downtown LM the late afternoon atmosphere was trigger

taut. Hardly anybody was working. The sidewalk cafes, restaurants and bars were

filled with Portuguese. The subject on every tongue was the Frelimo takeover.

We sat at the Continental sidewalk cafe on the Avenida

Republica over tiny cups of strong black coffee and Constantino brandy. All

around us locals were drinking and jabbering, most of them men. The air was

vibrant with anger.

Streams of cars and trucks passed back and forth, some

filled with people flying Frelimo flags. A small saloon car came slowly past

full of noisy white students exuberantly waving large Frelimo banners from all

the windows and shouting slogans.

It was too much for one young soldier. He pulled off

his belt, charged the car and swung the buckle to shatter the windscreen.

The car jerked to a stop. In seconds a wave of

shirt-sleeved men rose from sidewalk tables and ran to it, all restraint

snapped by the spark of violence. More rushed from the other side of the

street. The car and students were surrounded by a bloodthirsty mob seeking

outlet for their rage.

They smashed the windows and toppled the car on its

side with the terrified students still inside. I was right there next to it

shooting with my Leica.

A passing patrol of military policemen stopped and

rescued the students. Civil police arrived and tried to control the growing

crowd. An officer, Commissioner Fernando Segurado, raised his splayed hand to

try to block my lens so I photographed him too. It made the front page.

The mob ignored the police, who gave up and left. Now

grown to several hundred, they swirled along the avenida to a building housing two

newspapers.

We tried to follow but they became aggressive so we

chose discretion over stupidity and went to the fourth-floor rooftop of the

Tivoli hotel where we could look right down on them.

They rolled a delivery van on to its roof and

overturned two cars. They smashed the newspaper building’s windows and kicked

in the glass double door.

|

| Newspaper car overturned by anti-Frelimo rebels |

Oh God, I thought, Ruphin’s had it, the bloody novice,

he’s dead meat. And then, astonishingly, they let him go, brushed him off and

waved him on his way. He waved back and ambled on, leaving a trail of tobacco

smoke that must have been as bad as teargas.

A few minutes later he arrived on our rooftop. They thought

he was a newspaperman, he said, until he explained in French that he was an

innocent tourist accidentally caught up in all this fascinating activity.

Tourist was a buzzword in LM. They apologised and let him go.

|

| Cafe wrecked by Frelimo rioters |

That night the tensions exploded into widespread

violence. Exuberant mobs of Frelimo supporters roamed the black bairros

(suburbs) which almost surrounded the city’s landward side, stoning cars and

traders’ shops.

Mobs of hysterical anti-Frelimo protesters plunged

other city suburbs into chaos. About a hundred people raided a hostel and

offices near the university, whose students were prominent in pro-Frelimo

demonstrations. They methodically smashed plate glass windows while soldiers

and police watched, then went inside. When everything was wrecked, the police made

them leave. There was no doubt whose side they were on.

A dim-witted student shouted “Long live Frelimo!” The

mob descended on him with chairs from a nearby sidewalk cafe and would have

killed him had a passing army patrol not rescued him.

Some of the mob grabbed the barrels of their automatic

rifles and tried to wrest them away. They stopped when the soldiers cocked

their guns with ominous clicks.

|

| Sumptuous lunch at the Polana |

When it was over we retired to the exuberant décor of

the Polana, sipped salted dogs at its comfortable bar and enjoyed a sumptuous

dinner. War was a zillion miles away. It was a tough life.

In the dead of that night some clever rebels managed

to elude troops guarding an ammunition dump outside LM and set it on fire. It

blew up with a thump felt all over the city.

The next morning, after a leisurely breakfast of

smoked salmon and scrambled eggs on the Polana verandah, we went downtown to

watch as noisy cavalcades of cars filled with yelling young right-wingers

waving Portuguese flags, led by motorcycles and buzzbikes with horns blaring.

Truckloads of blacks flaunting Frelimo banners passed

them going to the Machava stadium for another mass gathering. White men leaped

from their cars and tried to rip away the Frelimo flags. The confrontation was

about to erupt into violence when traffic police, of all people, stopped it by

moving the vehicles on.

The city was grinding to a halt. Water and electricity

stopped when gangs stoned city vehicles in the bairros. A general strike by

black workers shut down the remaining services and shops. Most whites stayed at

home or settled down in a few cafes open for business to watch the fun, but

tempers were fraying.

“20 000 Back Frelimo at Giant Rally in LM”

“ROVING MOB KILLS MAN IN TENSE LM”

“LM stops work as Frelimo hailed”

“Mobs run amok in LM”

“LM WHITES SMASH INTO PRISON – SET DGS MEN FREE”

“LM on brink of anarchy”

“LOURENÇO MARQUES HAS NIGHT OF VIOLENCE AS MOB RIOTS.”

The handover was due at midnight, September 7,

technically ending four centuries of Lisbon rule.

It had no visible effect. After dark trouble spread. In

Beira a grenade was tossed into a bank and angry crowds roamed the streets.

In LM a large crowd smashed into the civil prison in

the Polana suburb to free about 200 members of the former Portuguese political

police who were arrested after the coup. They also released one of South

Africa’s most wanted men, the notorious criminal Carlos Rocha.

The prison was not far from the Polana hotel but could

have been on another continent as far as the guests were concerned.

|

| A temporary victory |

To distract the guards the crowd battered and

overturned the prison commissioner’s car parked outside and threatened to set

the whole prison alight. To back their threat they drove up a large truck and aimed

it at the main door.

Others from the crowd went to the door marked by Rocha

and rocked it until the lock snapped. They threw it wide and burst into the

prison.

Confronting them were rows of soldiers armed with

automatic weapons. Here was the recipe for a massacre.

It did not happen because people in the mob happily

hugged the soldiers and told them “You can’t shoot us, we are also Portuguese.”

The security policemen fled, most to South Africa

where many were taken into our Security Police and various Defence Force units.

By this time we were being run off our feet, trying to

follow incidents all over the city almost around the clock. We were living on

adrenalin supplemented by Laurentina beer, still in copious supply, thank God.

So I borrowed a reporter and a photographer from The

Star and sent them to Beira, the new hotspot.

|

| A tense moment |

Those coming by road had to run a gauntlet of blacks

enraged by the actions of the whites in LM. Some were stopped by mobs armed

with clubs and pangas who banged on the roofs of their cars and made them get

out, stole their cigarettes and whisky and let them go reluctantly when they

identified themselves as British.

At a road block one watched a black man beside the car

sharpening the blade of a large panga on the tarmac. The man glanced up and

grinned evilly at him as if he was next on the menu. They saw shops being plundered

and fired and a burning car with two dead people in it, presumably whites.

Taxis ceased to run in LM and we needed a car. The

Star sent me a Peugeot driven by Deon, a bright young reporter who brought with

him a photographer and a couple of other journalists. Approaching LM they were

brought to a stop by blacks manning crude road blocks.

Any attempt to barge through would bring certain

death. Deon summoned all his persuasive talents and they let him through.

The consumption of liquor in the Polana soared that

evening.

Wilf Nussey - TO BE CONTINUED

Wilf, I sure hope Ruphin will feature prominently in your novel. I love his style...

ReplyDeleteAnd this is fascinating stuff! Thanks for sharing.