Ovidia--every other Tuesday

On the domestic front, renovations are pretty much done (and our bathroom looks Fantastic) except for a couple of things they promise will be done by the end of this week--or by the end of next week...

On the work front I've wrapped up and set one project aside--well salted and spiced--to ferment (studying how kimchi is made wasn't a waste of time!) and will spend the next two weeks figuring out the next book... which will probably be set in a rubber plantation, hence today's post!

Growing up in Singapore in the 60's, there were rubber trees and rubber seeds pretty much everywhere.

I remember finding seeds like this in the field outside our primary school building.

The fun thing about these rubber seeds was that if you rubbed them hard and fast on cement floors, they heated up enough to 'burn' when pressed against other people's arms or legs. (And no, I can't remember why we did that!)

Anyway, rubber trees were found pretty much everywhere and rubber was big business in the region, though there were no plantations in Singapore. And even though Hevea brasiliensis isn't indigenous to our region.

How that came about thanks to the 2 Henrys of today's post; Henry Wickham and Henry Ridley.

The first Henry, Henry Wickham, was a 'bio pirate'.

In 1876, at a time when South America was the world's largest producer of rubber, Wickham smuggled 70,000 rubber seeds out of Brazil as "academic specimens". This was a term generally used to classify (dead) animal or plant specimens, not viable seeds.

A museum in Peru (Museo Barco Historicos in Iquitos) describes Wickham's act as "the greatest act of biopiracy in the 19th century, and maybe in history" claiming the plantations Britain set up in her colonies as a result of his theft destroyed South America's rubber business.

Wickham and his rubber seeds arrived in the Royal Botanic Gardens at Kew and 2,700 of the 70,000 seeds were successfully germinated.

Britain then sent rubber seedlings from London to British Ceylon (now Sri Lanka), Batavia in the Dutch East Indies (now Jakarta in Indonesia), British Malaya (now Peninsular Malaysia)... and in June 1877, twenty two rubber seedlings arrived at the Botanic Gardens of Singapore (now still Singapore) where they came under the care of the second Henry: Sir Henry Nicholas (H.N.) Ridley.

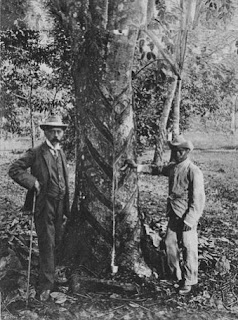

Henry Nicholas Ridley, a botanist by training and Scientific Director of the Singapore Botanic Gardens from 1888 to 1912. Shown above with the herring-bone method of tapping rubber that he invented.

Unlike traditional incisions that tended to kill trees, his method allowed for just a section of the bark to be removed to tap latex without destroying the tree.

Nicknames like 'Mad Ridley' and 'Rubber Ridley' show Ridley's passion for promoting rubber and its huge economic potential.

Ridley also researched the most suitable land and soil for planting, the ideal density per acre (instructing trees be planted 13 feet apart), the best method of raising seedlings, the most effective processing techniques, and the best means of packing and shipping processed rubber.

At the time, there was a huge demand for rubber in the West because of the exploding automobile industry and Dunlop's new pneumatic (rubber) tyres. But farmers were reluctant, because rubber trees took six years to come to maturity, compared to much quicker returns on tapioca, sugar and (especially) coffee.

What really made rubber take off in our region was when the coffee plantations, a staple crop till then, were wiped out by disease--making rubber the best alternative.

In the forests of Amazonia, the traditional tapping method had migrant workers searching out wild trees and leaving them to die after tapping. Under Ridley's guidance, British run Asian rubber plantations were far more efficient and were soon supplying more than 90 percent of the world's rubber needs.

Rubber trees (like so many of us) are a non-native species flourishing here as a result of British colonisation.

I didn't know this biopiracy story. We tend to think of it as something modern. Yet, the addition of harvesting without killing the trees did add something valuable. Thanks, Ovidia. (And good luck with the bathroom!)

ReplyDeleteThank you, Michael!

ReplyDeleteI also didn't know this story and it makes me want to go down a very deep biopiracy rabbit hole. Thank you so much for posting and hope the work is finished soon so you can live in peace. x

ReplyDeleteThis is fascinating. I had never thought about biopiracy before about a month ago, when I happened to hear a podcast about an Englishman stealing tea seedlings from China to plant in India, ultimately successfully and greatly to England's advantage. (It was a longer and more complicated story than I'm making it sound). And now this story about rubber. It makes me curious how common this has been throughout history.

ReplyDeleteWonderful, Ovidia. You have given me my subject of my blog next Monday!! AA

ReplyDelete