Wendall -- every other Thursday

As I was proofreading my latest book, I fell into the habit of listening to stand-up comedy specials in the background. It made me consider the boundaries of comedy in the modern landscape. So, I decided to revisit some thoughts I wrote several years ago about pushing the limits of believability, and screwball comedy, in a mystery.

|

| Comedy - gliding or colliding in Charlie Chaplin's 1916 film, The Rink. |

Suspending our disbelief has become a national pastime.

While it can be alarming in real life, Coleridge’s concept is usually something

fiction readers embrace. But where’s the line between delight and cognitive

dissonance, between a gasp and a guffaw, or in my case, a loud, sarcastic “Pleeeease,”

or “You’ve got to be kidding,” snorted across the living room?

On the surface, fantasy and sci-fi may be in more obvious need of our psychic

largesse, but mystery novels require their share, particularly if they involve

weekly corpses in a sleepy seaside town, sleuthing kittens, coffee roasters who

put the FBI to shame, or for that matter, justice.

|

| Is the justice served out in traditional mysteries something that belongs in a fantasy novel? |

Despite its body count, I believe our genre is a hopeful one. Crime novels are a place where wrongs are occasionally righted and characters—however flawed—can win, or at least have a shot at redemption. So it’s more important than ever not to betray our readers by pulling them out of the story. Where is that line we can’t cross? How much leeway do we have?

My conclusion, which is certainly up for debate, is a lot.

Successful writers across the genre push the bounds of believability all the time. Take Lee Child’s Jack Reacher. Can he really keep a toothbrush in his pocket while obliterating eighteen bikers? Can he actually find clothes that fit perfectly in the middle of nowhere, every single time his are dirty/bloody, when I can barely do it with an entire mall and the internet at my disposal?

Of course he can, because Child made sure Reacher was larger than life from the start—in every novel he accomplishes things which would seem impossible for a normal person. And because his wardrobe, or lack thereof, brilliantly supports and illuminates his restlessness and the impermanence of his life, we don’t care that it’s unlikely every small town surplus store carries khakis for giants.

|

| The immortal Rex. |

Janet Evanovich offers us the world’s oldest hamster—Stephanie Plum’s Rex. What

is he, thirty? Who cares? I hope he lives to be a hundred. Stephanie’s

been through enough.

As a reader, I will put up with a certain amount of coincidence, a couple of

“wait a minute, didn’t she’s?” and some leaps in logic, as long as I’m

connected to the characters and the book feels emotionally truthful and

consistent with the tone the writer established in the early pages.

As a writer, though, I’ve struggled to determine how much artistic license

writing a “zany” mystery gives me, when it comes to the details of plot and

character. I started out as a film writer, operating in a realm where nothing

was expected to be realistic, but are the rules different for novelists? Do

comedies get a pass hard-boiled books don’t? Or are the rules the same for any

imaginary world?

In my particular case, my first novel, Lost Luggage, had an amateur sleuth in Cyd Redondo, but a zanier tone than most traditional or cozy mysteries. So I turned to my inspiration--screwball film comedies--for a working "logic threshold."

|

| Is there a believable moment in this movie? Do we care? |

How did the whole leopard thing really work in Bringing Up Baby? Did Katherine Hepburn’s Susan Vance have a leopard litter box the size of a bathtub, off screen? Would she really wear a floor-length chiffon peignoir with claws around? Did it matter? I embraced every silly moment of that film, because writers Hagar Wilde and Dudley Nichols set up Hepburn’s character to repel logic from her first line of dialogue. And because it’s the tension between what is happening on screen and what should reasonably be happening which makes the film a classic.

|

| The Professors and the Showgirl. Ball of Fire (1941). |

Would Garbo’s Russian bureaucrat in Ninotchka actually wear

that ludicrous hat, or would eight bachelor scholars take in a gangster’s moll

in Ball of Fire? If Billy Wilder and Charles Brackett were writing

it, absolutely, because they gave us a beautifully crafted “suspension bridge”

from the first moment of both films, making their characters believable in all

their glorious unreality.

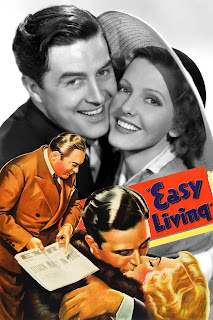

When Preston Sturges opens his script for Easy Living with a

Fifth Avenue millionaire’s mink coat landing on broke heroine Jean Arthur’s

head, we have no problem believing she will unwittingly meet and fall in love

with the millionaire’s son. We know right away we’re in a world where no

coincidence or happy accident is too great.

|

| One of Preston Sturges's early scripts. |

Still, as I’ve struggled throughout my series to maintain the tone one reviewer kindly called “enchantingly ridiculous,” I'm always wary of the line which might push it into the merely “ridiculous.”

In the end, it came down to listening to my character’s internal logic to make sure all my comic set pieces unfolded in a way that was believable for her and for the tone of the series. I found it also helped to try to keep up a relentless pace. That’s the true genius of the screwball comedies of the 1930s and 40s—their pace doesn’t leave the audience time to question or ponder. So that’s what I’ve tried to do in the series to date—write Cyd’s true, eccentric nature, as fast as I can.

|

| Will readers believe Cyd, who can't swim, will survive this drop? |

Whether readers buy her lowering herself on a rope—with her carry-ons—from a helicopter onto a cruise ship, preserving blood from a corpse in a travel nail polish bottle, rescuing endangered songbird eggs with her balconette bra, surviving a thirty foot drop from one infinity pool into another, or defeating the villain with her intimate knowledge of the way wheelchairs work, is always something I wonder, and worry, about.

How do you “cheat” logic or push believability in your novels and, as a reader, where do you draw the line?

--Wendall

I read this bit, about Reacher: 'Can he actually find clothes that fit perfectly in the middle of nowhere, every single time his are dirty/bloody, when I can barely do it with an entire mall and the internet at my disposal?' And I have to ask, Wendall, what are you doing that *your* clothes are getting dirty/bloody?!

ReplyDeleteI have occasionally been accused of Charlie Fox's self-defence skills not being capable of taking out a larger opponent. Whereas I know they'd work, mostly because I've tried 'em...

This comment has been removed by the author.

Delete(Charlie's a she...)

DeleteWhat a great piece, Wendall! Thanks. We try to keep things very close to reality in our books, but I suspect that most readers don't care that much. It's happening in Botswana, so who knows what happens there anyway? (Other than us.)

ReplyDeleteNevertheless there are counter examples. In one book, we write about a problem with the gas supply to a police Landrover. One reader wrote in to point out that, at that time, the Botswana police only had diesel vehicles... He still liked the book though!

PS We NEVER have Kubu go clothes shopping!

DeleteMichael, I always believe every word of your books, so whatever you are doing, it's working. I have to say, you might have to do a post about Kubu's shopping habits, someday! Thanks for commenting, as ever.

ReplyDeleteIt's a balancing act: the more enjoyable the writing, the less 'belief' is a critical component; and the "mistake-ishness" is also a critical factor: if the item in question appears to be intentional, for purposes of the story, the reader can roll along, but if it appears to simply be a mistake, with no apparent "story reason" for it to be there, then disbelief explodes.

ReplyDeleteHi Everett. I think you've summed the issue up brilliantly. Exactly right. Sadly, sometimes it's easier to understand what you should do, than to do it!

ReplyDeleteI recall Manda Scott talking about her book Boudica. She wrote that a horse fell due to putting a hoof in a rabbit hole. At a time when there were no rabbits in GB. She's a Cambridge scholar very clever type, and happily talks about her 'How Did I Get That Wrong Moment.'. But of her many books, that's the one everybody remembers!

ReplyDeleteCaro- isn't that always the way! Poor Manda Scott. There are so many places in an historical to stumble, and when you combine that with the current landscape where readers are able to publicly shame anyone, for any error,it's a rabbit hole in itself.

ReplyDeleteWhat a great column. This is an issue I struggle with on every Flynn novel. How absurd is too absurd? When does a joke push things too far, break the suspension of disbelief, and kill the suspense? I do sometimes think I cross the line. But I always try to keep the story grounded in some semblance of reality. (Whatever that is.) It's a tough balance. You pull it off well. Satire is so tricky today. So much of what's happening in the news is so insane and ridiculous...it's hard to compete.

ReplyDeleteHi Haris, I know you face exactly the same challenges I do in your series, although to my mind, you never stumble at all! The question of satire in an age like ours is a much bigger question, I think.

ReplyDeleteThis is a great piece! I think the reality disconnect helps sometimes though, when I'm reading to escape. I love zany Cyd!

ReplyDeleteHow kind of you, Ovidia. The fact that you think the disconnect helps, is highly encouraging! x

ReplyDelete