Wendall—every other Thursday

As I am a bit stuck at the moment, I'm revisiting this post and these writers to get me back on track to write during my break from UCLA. Happy Holidays, everyone!

As an author, this is a difficult thing to admit: I’m hard on books.

|

| This is the state of my original university copy of The Portrait of a Lady. |

If I love them, I reread them. A lot. I carry them in my backpack, I read them on buses while trying to balance a coffee, they fall on the floor when I fall sleep in the middle of a page, and if I think the line or the paragraph is something I want to remember, yes, I will star or underline. I was a huge underliner in college.

|

| The shocking inside of the book, above. |

For old hardback books, I do use Levenger’s gold page markers, at least.

|

| These Levenger page tabs are a lifesaver when you just can't bear to desecrate a book. |

When a beloved paperback starts falling apart, though, I have been known to hold it together with a rubber band, a trick I learned from my advisor, Bob Bain, as I don’t want a new copy—I would lose all my notes!

|

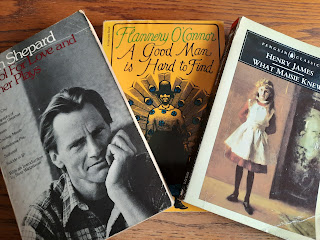

| Two that I just can't abandon, despite the state they're in. |

I hope that I read widely (I may be deluded, see below), even though there are hundreds of thousands of works I still need to get to. There are certain books that had a huge influence on me as a child that I revisit once a year, including Harriet the Spy, Alice’s Adventures Through the Looking Glass, and David Copperfield.

But there are three American authors I find most helpful when I am stuck, who offer inspiration and a way to understand the writing life, and who remind me of why I do this at all. Their books are especially beloved. And battered. Henry James, Flannery O’Connor, and Sam Shepherd.

|

| John Singer Sargent's portrait of James. I visit it in the National Portrait Gallery every time I'm in London. |

| |||

| One of my favorite photos of O'Connor. |

|

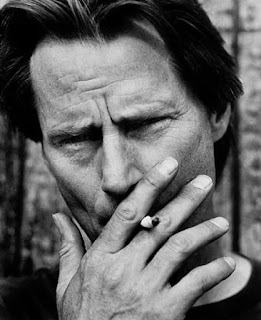

| Vintage Shephard, in a photo by Herb Ritts. |

They may seem a strange combination. They are certainly different in style. But to me, they all write about the same thing: the ways we delude ourselves. All of their works examine the fine line between having an imagination and flat-out lying, and the disconnect between the way people are perceived by others and the way they perceive themselves.

James’s Isabel Archer is one of the great “lying to herself” characters of all time, O’Connor reveals layers of tragic delusion through the grandmother in “A Good Man in Hard to Find” or Mrs. Shortley in “The Displaced Person,” and every character in Shepherd’s Buried Child is lying to themselves and everyone else, until they’re forced to face the truth in their backyard.

This is a topic that fascinates me, partly because, as a writer, our job is to make things up. So we have to be good at it, but can that spill into our own, personal narratives? Trying to understand this has certainly helped me as a writer, particularly in learning to hint at the subtext in every situation, and to show the way characters try to cover things up in dialogue, while unwittingly revealing everything. Their dialogue has especially influenced me as a screenwriter.

I also think all three of them are, in their own ways, hilarious. I am in the preliminary stages of a new mystery series that features Henry James and he completely cracks me up. If I were casting him, I’d choose Bill Murray. The layers of irony and sarcasm in his work always take me by surprise, but they’re everywhere. Here’s an exchange from one of my favorite, more obscure stories, “The Beldonald Holbein.”

“What’s the matter with her?”

“Well, to begin with, she’s American.”

“But I thought that was the way of ways to get on.”

“It’s one of them. But it’s one of the ways of being awfully out of it too. There are so many!”

“So many Americans?” I asked.

“Yes, plenty of them,” Mrs. Munden sighed. “So many ways, I mean, of being one.”

|

| Bill Murray. From Dr. Venkman to HJ? |

O’Connor, of course, is famous for her zingy one-liners. “Everywhere I go people ask me if I think universities stifle writers. I think it doesn’t stifle enough of them.” When told that author Caroline Gordon did most of her writing while she did the dishes, O’Connor’s response was “I think there should be a complete separation between literature and dishwashing.” And this sentence from “Good Country People” delights me: “Besides the neutral expression she wore when she was alone, Mrs. Freeman had two others, forward and reverse, that she used for all her human dealings.”

Shephard’s characters are so often defined by absurdist, darkly comic lines like True West’s “There's gonna be a general lack of toast in the neighborhood this morning.” Or Buried Child’s “You should take a pill for that! I don’t see why you just don’t take a pill! Be done with it once and for all. Put a stop to it. It’s not Christian but it works.”

Of course, for all three, the humor is one gateway to the serious topics they’re taking on. This is probably why all three of them are also famously cranky. As someone who was taught it was impolite to be cranky at all, but especially in public, I adore that they snap at people and never suffer fools gladly. This always gives me a vicarious thrill.

|

| I love this photo of HJ. What writer hasn't had this kind of day? |

But maybe I love them most for their other writings—letters, notebooks, interviews, introductions—because they offer a window into the way they work. They certainly all suffered from doubts and missteps, but from what I can tell, all of them learned to trust that they were a conduit for art, that if they showed up, the words would come through them. As a “pantser” I find this comforting.

O’Connor: “I sit there by the typewriter for three hours every morning and if something comes, I am there to receive it.”

Shepherd: “I felt kind of like a weird stenographer. I don’t mean to make it sound like hallucination, but there were definitely things there, and I was just putting them down.”

James: “Well, that is my start—and the rest ought to go. I can trust myself.”

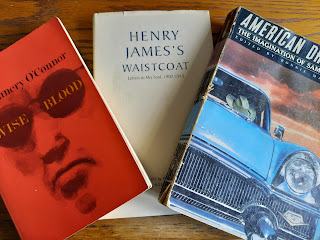

My particular favorite places to find these writers’ thoughts include The Complete Notebooks of Henry James, O’Connor’s collection of letters, The Habit of Being, and Conversations with Flannery O’Connor, and a new work which astounds me, Two Prospectors: The Letters of Sam Shephard and Johnny Dark.

|

| All underlined like mad, of course. |

I just hope I live long enough to rubber band these three.

--Wendall

Thanks for these insights, Wendall. I try to learn from John Le Carre, but haven't got to the rubber band stage yet...

ReplyDeleteHa! What a person to learn from and I can certainly see the same kind of suspense and complication he uses in your work. I don't recommend rubberbands, I just use them!

ReplyDeleteAs a fellow pantser, I find comfort in knowing I'm not alone in wondering why there are days when it's just my screen saver and me staring back at the other--one pleadingly, one relentlessly.

ReplyDeleteI hear you! I figure, if it happens to you, and to them, who am I to complain/tear my hair out. Thanks for commenting, Jeff.

DeleteHi Wendall: I have always felt that the two books that have influenced me the most are Alice's Adventures in Wonderland and On the Beach. The first for its power of iimagination; the second for its power of story.

ReplyDeleteAh, Stan. On the Beach! What an amazing book. And glad you are an Alice fan. I've always been delighted by yes, the sheer magnitude of the imagination there, and also Alice's attitude throughout! Thanks for commenting.

DeleteWhat a thoroughly enjoyable post! Thank you for such a rich share.

ReplyDeletePS, I have always liked Alice's Adventures in Wonderland, too.

DeleteElizabeth, thank you for your kind words and very glad you enjoyed the post. As I said above to Stan, I'm an Alice girl for good.

DeleteThank you for this post--it triggered me to go look up some of my old favourite reads that I've not visited recently enough too!

ReplyDeleteHi Ovidia. I do feel guilty sometimes, since there are so many new things to read, just from my mystery author friends alone, but it can nourish your soul by putting you in touch with how you felt when you first read them.

DeleteYour reading prowess puts me to shame!

ReplyDeleteHa! I just had some really good teachers.

Delete