Confession #1: My

taking up this subject was inspired by an episode of Radiolab, which is the

best radio program in the history of the universe. I have referred to it here before. You can find the episode about the Haber’s

life among the podcasts in their archive. http://www.radiolab.org/archive/

(If you are not a fan of the show, become one. It will enrich your mind and your

conversation.)

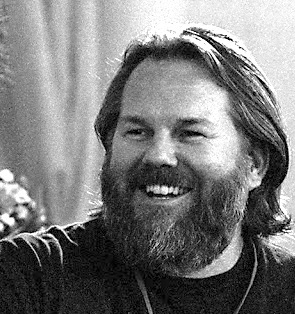

Confession #2: Until I learned about him on a Radiolab, I

had never heard of Fritz Haber. Now that

I know his story, I can’t figure out how to think about him.

Here he is. Tell me

what you think.

Fritz Haber was born in Breslau, Prussia (later, Germany) on

the 9th of December 1868 to a prosperous German-Jewish couple. The family owed a lot of its wellbeing to an

1812 edict that gave Jews something approaching full citizenship. Haber’s parents were first cousins who

married over the objections of his grandparents.

Fritz’s mother died three weeks after his birth, which

devastated his father and left him to be cared for by his mother’s and father’s

sisters. After that, though eventually he

got along well with his stepmother and half sisters, his relationship with his

father was always contentious. The young

man grew up to be fiercely patriotic and determined to succeed.

Despite his fraught relationship with his papa, the

brilliant young student prepared to go into his father’s successful business,

which specialized in dyes, paints and pharmaceuticals. He studied chemistry in the best

universities of Germany, including a stint as a student of Robert Bunsen, of

“burner” fame. He earned a PhD cum laude in chemistry at the age of 23.

The good work

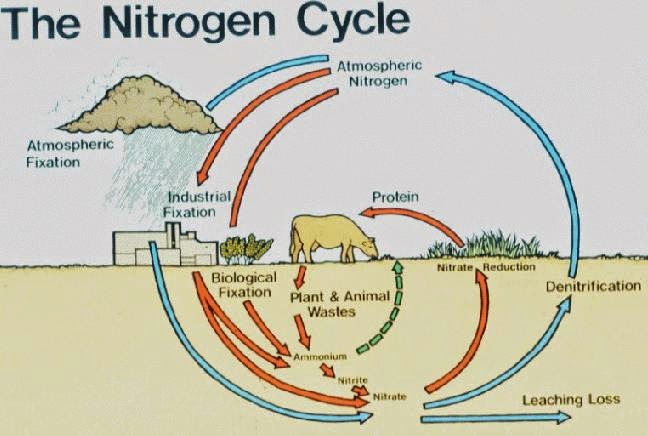

After bouncing around in several minor academic posts, he tackled the most serious problem facing his country—starvation. I know, “starving Germans” is not a phrase the leaps to mind these days, but at the turn of the Twentieth Century, the world food supply was quite limited, putting many people, including Germans, at risk. What was needed was nitrogen to boost agricultural yields. At the point, most fertilizer came from animal waste—bat guano, that sort of thing.

The air is full of nitrogen, but its chemical nature made

producing artificial fertilizer difficult in the extreme. (Nitrogen is trivalent. It fiercely clings to itself rather than

willingly forming molecules more easily collected.) The stubborn element met its match in

Haber. With monumental persistence, he

devised a process involving heat and high pressure that forced nitrogen to

combine with hydrogen and form ammonia.

Voila! Thanks to Haber and his

colleague Carl Bosch, the world food supply soared. “Bread from the Air” they called it. Today, half the world population owes its

existence to that boost in agriculture production. HALF of the seven billion people on this

planet (or their grandparents) would have starved to death without Haber. No kidding.

Haber received the 1918 Nobel Prize in Chemistry for his

discovery.

The bad work

The other side of the story is grim. Remember that I said Haber was fiercely

patriotic? By the time he was headed for

that Nobel Prize, Germany was at war.

Despite the Hague Convention of 1907, which proscribed chemical weapons,

Haber had a killer of an idea. As a

Captain with the Chemistry Section of the German Ministry of War, he lead a team

that weaponized chlorine gas. He went in

person to the Second Battle of Ypres in April of 1915. There he personally oversaw the release of a

green cloud that destroyed somewhere around 6000 lives; most died in the first

ten minutes.

Haber considered this a great achievement. When he got home to Germany, he threw himself a celebratory dinner party. At this point, he was married to Clara Immerwahr. They had a thirteen-year-old son. Clara was a remarkable scientist in her own right—one of the first women on the planet to earn a PhD in chemistry. She was so appalled by what her husband had done that after the dinner party, when Fritz had gone to sleep, she took his service revolver out to their back yard and shot herself in heart. Their son reached her before she died.

The very next morning, Fritz left his son and dead wife to return to the front so he could continue to use his gas to fight the war.

When Germany lost, Fritz was devastated. He spent years trying to extract gold from the ocean to pay their war reparations. But then, with the rise of Hitler, despite the fact that he had served Germany in the previous war and had converted to Christianity, he was not allowed to hold a university post. He left for England, where his wartime activities made him a pariah. He eventually made his way to Switzerland where very soon he died in 1934.

After his death, the most chillingly ironic thing

happened. In the 1920’s Haber and his

team had developed a cyanide-based gas used to fumigate grain stores. Zyklon-A was formulated with a telltale smell

that would keep people safe from accidently inhaling it. In the 30’s, when the Nazis were looking for

a mortal gas for their chambers of death, they reformulated Zyklon-A without

the safety odor. Zyklon-B became the

weapon of the Nazi Concentration Camps.

So what do you think?

Was Fritz Haber a good person or a bad person? Was he a boon to humankind or a curse?

Annamaria - Monday

Yikes! That's a difficult question. If I had to vote, I'd say good - with severe blemishes. He didn't intend the cyanide gas to be used to kill Jews. Or maybe I'd vote bad - with exceptions. He used his knowledge of chemistry to create outlawed weapons and celebrated when they succeeded, but he also helped to increase the world's food supply. As I said, Yikes - what a decision to make. I abstain.

ReplyDeleteMy sentiments exactly, Stan. It also occurred to me that all that food accounts for a lot of world population growth. It's so difficult to love human beings and to know that there are way too many of us. Haber benefitted billions more people than he harmed, but I cannot see him as a great humanitarian--not when he devised such an UGLY death for those poor soldiers at Ypres and then rejoiced in it.

DeleteThis is well done , but I confess anything about Hitler makes me see red!!!!!!! I saw some of the garbage from the Nazi submarines on our beach in Norfolk as a child and to this day - if I saw a Nazi uniform I'd turn into a wild savage! tstraw in manhattan

ReplyDeleteThelma, AGREED! In the immortal words of Indiana Jones, "Nazis, I hate those guys."

DeleteStan very well stated my exact thoughts. More positive than negative, but oh, my, what extremes.

ReplyDeleteUnfortunately, there's very little connection between intelligence and morality. You can have neither, one or the other, or both, two independent variables.

The great 'evil' of this story is "national pride," patriotism. It's an amoral "intellectual emotion" that leads people to do immoral things, because it creates a blindness against our shared humanity.

EvKa, I have always had trouble with patriotism as an emotion. If I feel it at all it is for my city, which I can say I really love. There are other places I love as places too. I cannot agree more that national pride leads to more wrongs than it does rights.

DeleteOn another note, we will meet up soon. Are there plans?

EvKa, you wrote: "The great 'evil' of this story is "national pride," patriotism. It's an amoral "intellectual emotion" that leads people to do immoral things, because it creates a blindness against our shared humanity." I couldn't agree more. Patriotism and its weak cousin jingoism should be sins.

DeleteAmA, yes, we will meet soon (10 days or so). Are there plans? No. Expectation? Yes. :-) I'm hoping to get together with you and Jeff (yes, I'm a brave and daring soul) at one point or another or maybe two. I noticed in the last newsletter from Crimelandia that they're setting up (or offering) "Author Hosted Tables" for the banquet. They want there to be two authors to a hosted table, apparently (they say, "If you are an author and would like to host a table, first find another author to co-host with you, and then email Lucinda Surber for more details." I (and Sharon) would love to share a table with you and Jeff, but that, of course, would require agreement and consent from both of you, who might have other plans and ideas. But it's a thought. What do you think? Jeff? I'm hoping to get together with Tim for lunch or something, too, at some point.

DeleteI am definitely up for sharing an author table with Jeff. Jeff, I dare you to refuse publicly. ;) I am also up for other social moments and any meeting with Tim is a pleasure for me.

DeleteDarrell James and I are already prom dates for the dinner. :( But I'm still available as a party favor, and otherwise free for the time I'm there.

DeleteThanks for posting about Haber--like you, I'd never heard of him before. While his work in agriculture yielded great benefits to mankind, I doubt Haber was motivated by altruism. He strikes me as amoral, focused solely on science rather than any regard for human beings.

ReplyDeleteYes, Allan. I see him that way. When it comes to human values, he was blinded by science. Brilliant, but chilly in the extreme. In fact, his motivation for the ammonia process was, according to what I learned, to feed hungry Germans, not hungry human beings. And I imagine the challenge inherent in the chemistry is what drove him.

DeleteI heard this Radiolab too!! I'm split about him, like you are. His activities during the war were so horrible that a part of me wishes he'd never lived...and yet, his other achievements saved more lives than the evil ones cost.

ReplyDeleteEven so...I don't think saving one human life "pays back" for taking another. On balance, he's a difficult person to think about. On the whole, I think I find him despicable - the kind of person of you say "well, I'm glad he did some good in his life, but I cannot understand how he justified the evil."

His life is definitely a cautionary tale against the evils of blind patriotism. Patriotism itself can be a wonderful, lovely thing - until and unless it makes you blind enough to cause suffering without conscience.

S, Despicable is good word. If you recall, the RadioLab guys said what he lacked was self-doubt. He seemed to have no capacity to question the worth of his own actions. If they served his purposes, they were right. There is something sociopathic about such an attitude.

DeleteIf you think about histories' great generals, they all conquered and slaughtered in the name of glory. Glory for country, glory for themselves? Whom or how many died at their hands did not matter...as long as they won. Hubris, patriotism, and all their self-aggrandizing relatives have long been slaughter's handmaiden.

ReplyDeleteWhat I wonder is when did Häber turn, and what brought him to lose his soul? Or was it simply the scientific challenge that drove him without regard to the practical consequences of his actions, ala "Bridge Over the River Kwai"?

As to debating whether he benefitted or debased humanity, to my way of thinking, it all depends on who's doing the scoring--with the ultimate scorer trumping all of us.

Jeff, I included some of his family background to try to give a picture of him as person, not just a chemist. But I think it was the scientific challenge more than anything that drove him. He is an enigma, that is for sure.

DeleteAnnamaria, you have two complex issues going on at the same time. One is the Faust-like personaolity of the scientist. Rarely are humanitarian concerns driving him. In fact, there has been a lot said about the similarities between a theoretical scientist and a drug addict. I would also take issue with the above about patriotism. The personality of a German Jew during Hitler's era will, I believe, have more to do with the need to prove "I am one of you," with belonging rather than patriotism. He sounds like a monster to me.

ReplyDeleteMr. Haber, was born a German Jew and designed a fertilizer to increase food production, which is still saving lives today. He did over see the use of his chlorine chemistry to kill 6000 soldiers in minutes! He may have thought it was humane to kill a great

ReplyDeletenumber in a short period of time and save his troops, rather than let them continue to shoot each other into submission! One can only speculate? However, he converts to Christianity during Hitlers rise, perhaps to save himself or his soul? Obviously, his wife taking her life to distance herself from him indicates her feelings of horror! We will all be judged one day. However, my consumption of a loaf of bread, in a sustainable way today, is related to him so, for that thank you Sir. I think a good man went bad then sought forgiveness. The pages of the Bible are filled with good men going bad and seeking forgiveness and repentance.