Wendall -- every other Thursday

Before I was a novelist, I was a screenwriter. I still teach screenwriting in the Graduate Film School at UCLA, so I still think about movies. A lot. Lately, I’ve been thinking about how all those hours watching every thing from The Wizard of Oz to The Verdict to Parasite have helped—and shaped—me as a mystery author.

My Cyd Redondo series started out as a script—my homage to the film Romancing the Stone—and eventually turned into Lost Luggage.

During my first draft, I stumbled onto Stephen King’s On Writing, which insisted authors “. . . must do two things above all other: read a lot and write a lot.”

I loved that advice, because it rationalized the pleasure and purpose I felt adding to my TBR pile. I’m no Stephen King, and movies and books are very different animals, but here are three reasons you can rationalize heading back into a dark cinema or picking up your remote as part of your ongoing education as an author.

# 1 CHARACTER BEHAVIOR

Over fifty percent of genre and commercial novels are written in the first person. Even in second or third person, novelists are allowed, and even encouraged, to describe what their characters are thinking and feeling. Screenwriters are not. Barring a constant voice over, a script must externalize thoughts, feelings, and backstory into concrete moments you can see or hear onscreen. Doing this well can be the hardest thing about film writing.

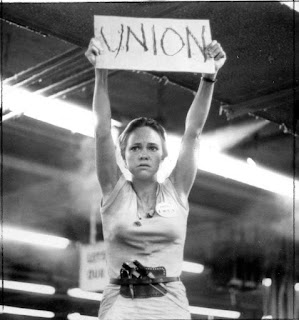

Luckily for us, screenwriters have actors to manifest these gestures, behaviors, and dialogue, so we can learn from them. In films, we can watch unspoken moments of commitment (Sally Field raising her “Union” sign in Norma Rae or Ingrid Bergman palming her Nazi husband’s key in Notorious), unrequited love (John Cusack holding up his boom box in Say Anything), friendship and compassion (Mahershala Ali teaching “Little” to swim in Moonlight), or the nervousness of attraction (Paul Giamatti babbling about Pinot in Sideways).

Breaking down what actors do in a scene—underneath and between the words—can inspire more use of action, variety, and subtext in our own fiction writing.

Sometimes we forget that always having access to a character’s inner thoughts can create stasis, particularly if the character is always telling the truth. A steady stream of truth might be a relief in real life, but in fiction, it can lack modulation and suspense. If you can let some of your characters’ internal thoughts hide in behavior and subtext, the truth—when it appears—can be twice as shocking, heart-wrenching, hilarious, or powerful.

# 2 THE VALUE OF SEQUENCES

Often what we remember about a film or show we love is actually a sequence—the bicycle chase in E.T., the christening/massacre in The Godfather, the wedding dress store/food poisoning sequence in Bridesmaids, or the opening Winnebago/underwear sequence in Breaking Bad.

Sequences—a series of scenes arranged around a central idea, location, or event—become “mini movies,” held together by repeated phrases, objects, characters, and backgrounds. They give us ups and downs, crises and resolutions, in the midst of the larger experience of the film. Most of us make a real effort to end a chapter on a cliffhanger or a great line. But how much do we really think about the interior construction of the chapter, all the reversals and connective tissue that come before that payoff? Sequences and chapters aren’t the same things, but the principals behind these “mini movies” can improve the pacing and the impact of your chapters as well as your overall book.

One of the most important elements of screenplay structure and of sequence writing is the Midpoint. In a script, the Midpoint destroys a character’s initial plan for dealing with their problem and necessitates a different approach or focus. Structurally, this energizes the story and re-engages the audience. Sequences work the same way.

There’s a famous one in Bringing Up Baby, which begins with Cary Grant’s entrance in a top hat and ends with his walking out attached to Katherine Hepburn. It’s a masterclass in sequence writing. The piece is held together by the recurring use of the top hat, olives, handbags, and pratfalls. But it’s most impressive for its Midpoint, in which a psychiatrist informs Hepburn that “the love impulse in man frequently reveals itself in terms of conflict,” turning her irritation with Grant into a romantic obsession. The power struggles between them from that point on escalate the comedy and lead to the climactic decision which ends the sequence.

To see whether you’re getting the most out of your chapter structure, you might pay attention to the sequences in Three Days of the Condor, The Shape of Water, Sicario, Four Weddings and a Funeral, Get Out, Parasite, or your favorite film, to see how great screenwriters use this principle to their advantage.

# 3 CLEAR, IMPACTFUL ENDINGS:

An executive at Disney maintains the last ten minutes of any film are the most important. No matter how good the rest of the movie is, if the ending is unsatisfying, that’s what the viewers remember and talk about. Fiction may be more forgiving, but I do think great films can teach us not to linger too long after the central question of the story’s been answered, to go out “with a bang, not a whimper.”

Whether the ending is a freeze-frame image of the characters’ final, climactic decision in Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid or Thelma and Louise, a single, memorable line after the heartbreaking goodbye in Casablanca, Roy Scheider and Richard Dreyfuss paddling home once the shark is dead in Jaws, or one heartwrenching look between teacher and student at the end of the defiant drum solo in Whiplash, films teach us to deliver an ending the whole story has been working towards, and not to diminish that moment by hanging around too long to wrap things up.

So, go ahead and watch your favorite movie. It might be the stuff novels are made of.

---Wendall

Thanks, Wendall. A lot to think about there. I recall in On Writing, Stephen King says he always carries a book with him, and uses any spare time to read. Good advice!

ReplyDeleteHe's the master! Well, after Henry James. Thanks for reading.

DeleteHe's the master! Well, after Henry James. Thanks for reading.

ReplyDeleteYou used so many great examples from movies, Wendall. This was a helpful post that made me think about how I construct a chapter. I especially like your point about not providing a steady stream of truth from your characters' minds or mouths because it takes away suspense.

ReplyDeleteHow kind of you to say, Kim! Thanks for reading.

DeleteHaving also worked as a screenwriter and playwright, I incorporate a lot of these techniques instinctively. But I love how you broke them down and really examined how those techniques can really work for novels. I'm always thinking in sequences. We also called them set pieces. And I build a few into every book I write. For me, it makes the writing easier. Each one has a beginning, middle, and end, changes up the story, propels it into a new direction. I'm always thinking of reversals and twists and the big one at the mid-point. Being able to show the character's thoughts can indeed be a crutch, which is why I don't write my books in first person, but love delving into every character's head to show all the conflicting versions of reality. How they lie to themselves as much as they lie to everyone else. And why I also like revealing much of that through character behavior and dialogue. Thank you for exploring these techniques and explaining them in such great detail. I'm sorry I never took one of your classes.

ReplyDeleteHaris! I'm so glad you agree, especially about the mid-point. Means so much coming from you. I'm doing my first clse third right now, and I may need your advice! Hope you are well.

Delete