Stanley - Thursday

When I was a kid, my family went on a BIG outing to Sterkfontein Caves, about 40 kms northwest of Johannesburg. We, the kids, were eager to see if we could find Mr Ples, husband to the legendary Mrs Ples.

To set the stage for the visit, I need to go back a few years. In the late 1800s, some limestone miners were the first to notice fossils embedded in the rock at Sterkfontein. They were smart enough to bring them to the notice of scientists.

However it was only in 1936 that the first of a series of startling discoveries were made at Sterkfontein. Students of Drs Raymond Dart and Robert Broom from my alma mater, the University of the Witwatersrand, unearthed the first adult Australopithecine, which reinforced Dart's claim that remains found at a place called Taungs by quarrymen and named Australopithecus Africanus - the southern ape from Africa - "was an extinct race of apes intermediate between living anthropoids and man". The paper appeared in the 7 February 1925 issue of the journal Nature. The fossil was soon nicknamed the Taung Child. For a variety of reasons, most scientists initially rejected Dart's theory. (If you are interested in conflict and dissension in the scientific community, it's worth reading Taung Child.)

|

| Taung's Child |

It was the discovery of the Australopithecine at Sterkfontein that caused the tide to turn with respect to acce[ptance of Dart's theory.

Back to Mrs Ples! After World War II, Broom continued to work at Sterkfontein and found a nearly complete female skull, which was classified as Plesianthropus transvaalensis, but quickly came known as Mrs Ples. It is now classified as an Australopithecus Africanus, and was thought to be about 2.1 million years old, much more recent than Lucy, the Australopithecine found in Ethiopia by Donald Johnson, which is thought to be 3.2 million years old. (It's interesting to note that Lucy got her name because the Beatle's song Lucy in the Sky with Diamonds was played incessantly at the dig.)

|

| Mrs Ples |

So, off my family went in search of Mrs Ples's wayward husband. We were unsuccessful.

However, Sterkfontein was not finished with what it had to offer. In 1997, a nearly complete skeleton of a second species of Australopithecus was found in the caves by Ronald J Clarke. Extraction of the remains from the surrounding breccia is still ongoing. The skeleton was named Little Foot, since the first parts found (actually, in storage, in 1995) were the bones of a foot.

To date, Sterkfontein has yielded over 500 hominids, making it the richest site in Africa and one of the richest anywhere.

In 1999, UNESCO declared the area around Sterkfontein a World Heritage site, which currently occupies 47,000 hectares (180 sq mi) and contains a complex system of limestone caves. It is known as the Cradle of Humankind and has a fascinating interpretative centre.

But wait, there's more.On 13 September 2013, while exploring the Rising Star caves in the Cradle of Humankind, two cavers, Rick Hunter and Steven Tucker, found hominem fossils, that were to become known as Homo Naledi, dated to about 335,000–236,000 years ago.

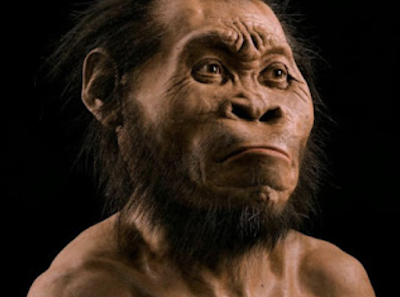

Artist's rendering of Homo Naledi.

You can read about this amazing discovery, as well as the remarkable actions that had to be taken by lead investigator Prof Lee Berger and his team of cave astronauts - all female! - in Michael's wonderful blog written in September 2015.

Remarkably, the Naledi discovery followed another astonishing find - by Berger's son Matthew in 2008 - namely Australopithecus Sediba. The skeletons are about 2 million years old and almost complete.

This is Matthew Berger

This is Australopithecus Sediba

Needless to say, each find ignites discussion and controversy as to where it fits into both the historic timeframe and genealogy of modern humans. It has been generally accepted that Lucy is about 3 or so million years old, while the oldest finds at Sterkfontein were thought to be considerably younger. This then led to the belief that East Africa was the more likely origin of the earliest hominin that eventually evolved into the Homo genus we belong to.

But wait, there's even more!

A study published this week found the some of the Australopithecus fossils are a million years older that previously though and are about 3.4 million to 3.6 million years. This puts them around the same time as Lucy and others in East Africa. The researchers, including experts from Johannesburg and France, examined radioactive decay in rocks buried at the same time as the fossils, whereas earlier estimates were based on calcite flowstone deposits.

The study indicates that the South African hominins, which had been considered “too young” to be ancestors of the Homo genus, were actually “contemporaries” of those in East Africa and had the time to evolve, said Dominic Stratford, director of research at the caves and one of the paper’s authors.

“This important new dating work pushes the age of some of the most interesting fossils in human evolution research, and one of South Africa’s most iconic fossils, Mrs. Ples, back a million years to a time when, in East Africa, we find other iconic early hominins like Lucy,” he said.

Quite frankly, I don't understand very much about any of this, but what I do know is that the caves I crawled through when a kid, looking for Mr Ples have yielded unbelievable riches in our quest to understand our origins. If you visit South Africa, a visit to the Cradle of Humankind should be near the top of your list.

Maropeng Visitor Centre at the Cradle of Humankind

It's a wonderful story of human evolution. Thanks, Stan. Let's hope the Supreme Court doesn't ban that next!

ReplyDeleteIt's comforting--in a strange sort of way--to realize that life "akin" to how we look today dates back millions of years. It gives me comfort that our descendants shall survive this #@#&* Supreme Court. In that vein, is it just me or does the artist rendering of Homo Naledi resemble actor Willem Dafoe--whom I genuinely admire.

ReplyDelete