|

| Wes Studi and Adam Beach as Joe Leaphorn and Jim Chee in a TV adaptation of Tony Hillerman's Navajo Mysteries |

Craig every second Tuesday

Kia ora and gidday everyone.

Can you believe it's the end of November already, and we're hurtling towards the festive season (or already started it in some places and cultures) and the end of 2021? What a year it's been.

It's also that time of year when many magazines, newspapers, podcasts etc are sharing their 'best of the year' lists, including best books. I've contributed to some, and shared others. Lots of amazing reads - in a troubled time we've certainly been blessed with some superb crime writing, at least.

Over the past weekend I was involved with the Terror Australis Readers and Writers Festival, a wonderful event that was intended to be a hybrid festival somewhat like this year's Bloody Scotland - having in-person events in Tasmania alongside international authors and attendees appearing online - that in the end had to go fully online after recent COVID concerns in Australia.

|

| Australian booklover Romany Jane shared this pic of her enjoying my interview with Queen of Crime Val McDermid over breakfast. The beauty of online festivals! |

It was a heck of a lineup, with international crime fiction stars including Val McDermid, Liz Nugent, Ann Cleeves, Abir Mukherjee, David Heska Wanbli Weiden, and Naomi Hirahara joining a wonderful array of Australian and New Zealand crime writers for a weekend of interviews, author panels, masterclasses, and book parties. I had the good fortune to bookend the festival by interviewing Val to kickstart things on Saturday morning, and Abir to close out the festival on Sunday evening.

In between I also spoke at the Southern Cross Crime Cocktail Party showcasing 20 Aussie & Kiwi crime writers, and had the privilege of interviewing International Guest of Honour David Heska Wanbli Weiden, a Lakota Sicangu author whose wonderful debut WINTER COUNTS has gobbled awards in the United States since its release, and has recently become available in the UK, Australia, and NZ.

|

| My feature in the New Zealand Listener on David Heska Wanbli Weiden and WINTER COUNTS, recently published in Australia and New Zealand |

WINTER COUNTS is one of my favourite reads of the last couple of years, the 'pandemic years' if you will, and I've been fortunate enough to interview David a few times this year for festivals, podcasts, and the New Zealand Listener magazine. You can listen to our CrimeTime FM conversation here.

I've long been interested in Native American culture, and have spent a small amount of time on the Navajo Nation and Cherokee reservations when travelling in the United States in years past. But until I read WINTER COUNTS last year (I ordered the US hardcover on the recommendation of SA Cosby, author of BLACKTOP WASTELAND), the only crime fiction I'd read with Native American protagonists was written by non-native authors like Tony Hillerman and Dana Stabenow.

While Wanbli Weiden is a fan of Hillerman's mysteries starring Navajo sleuths Joe Leaphorn and Jim Chee, it's great to see a Native-written thriller now getting lots of acclaim and attention too.

Of course, Wanbli Weiden is not the first Native American crime writer, but hopefully his recent success - WINTER COUNTS has already won nine awards in the United States, including sweeping the Macavity, Barry, and Anthony Awards for Best First Mystery this year - will bring more attention and open doors just as Larsson and Mankell did for Scandi Crime and Jane Harper did for Australian crime.

Today is the last day of November (which is Native American Heritage Month in the United States) and given I've been thinking about this topic after speaking with David again recently, and we should read indigenous authors all year round, here are seven Native American authors you may want to try (some I've bought and read on David's recommendation, plus a few others) in the coming weeks and months.

|

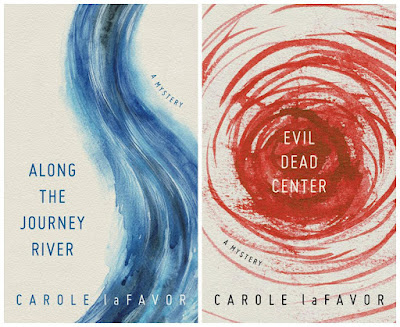

| laFavor's ground-breaking crime novels were re-released by the University of Minnesote Press in 2017, six years after the author and activist passed away. |

CAROLE LAFAVOR

A Two-Spirit Ojibwe novelist, nurse, and activist who lived and worked in Minnesota, laFavor published two crime novels in the late 1990s, around the time she was serving as the only Native American member of the of the President's Advisory Council on HIV/AIDS. ALONG THE JOURNEY RIVER introduces Renee LaRoche (likely the first queer protagonist in Native crime fiction), who must investigate the theft of several sacred artefacts and the murder of the Tribal Chairman while juggling the cultural differences in her new relationship with a white woman.

"Ultimately the re-release of Carole laFavor’s novels serves to underscore the significance of her writing to the Indigenous literary canon, to remind us of the power of her activism for HIV-positive Native peoples, and to return her important claims for the centrality of Two-Spirit peoples, bodies, and histories to the public eye," said Lisa Tatonetti in the Foreword to the new 2017 editions.

|

| David Heska Wanbli Weiden is a Professor of Native American Studies in Denver and an enrolled member of the Lakota Sicangu Nation. |

DAVID HESKA WANBLI WEIDEN

As I said above, WINTER COUNTS is one of my top reads of the past couple of years. It's a powerful thriller set on the Rosebud Indian Reservation in South Dakota, beautifully written and laced with themes of a broken criminal justice system and native identity. Virgil Wounded Horse is a tribal enforcer on the reservation, available for hire by victims and their families who are looking for some sort of justice when the FBI and tribal police fail. But when heroin threatens the rez, and Virgil's nephew, he undertakes a dangerous investigation into those who profit from others' pain.

This is a thriller with heart and soul. The kind of book that sticks with you beyond the events that have you rapidly turning the pages. Character-centric crime fiction that packs a punch in a setting that pulses through its lyrical prose. For me - and many other readers, critics, and awards judges, it seems - WINTER COUNTS marks the arrival of a strong new voice in crime fiction.

|

| An expert on John Steinbeck and pioneer of Native American Studies, Louis Owens won the Roman Noir Award in France in 1995 for THE SHARPEST SIGHT |

LOUIS OWENS

The first time I discussed Native American crime fiction with Wanbli Weiden, he immediately named Louis Owens as in his view "the most important" Native crime writer. A Professor of English and Native American Studies and the Director of Creative Writing at UC-Davis before his suicide in 2002, Owens blended thriller plots with broader themes, murder mysteries with mysticism in novels like THE SHARPEST SIGHT, BONE GAME, and NIGHTLAND.

Says Wanbli Weiden: "His books are not really page-turners, but he pioneered a style of crime fiction which sort of set the stage. He incorporated a call for political action, social commentary, and a surrealistic style. There’s something really interesting about Louis Owens; he’s not really included in the canon of great crime writers and I’ve been arguing for a long time that he should."

|

| Chippewa poet and novelist Louise Erdrich won the National Book Award in 2012 for THE ROUND HOUSE, her tale of a teenager attempting to avenge his mother's rape |

LOUISE ERDRICH

Considered 'one of the most significant writers of the second wave of the Native American Renaissance', Louise Erdrich is a poet, novelist, children's author and member of the Turtle Mountain Band of Chippewa Indians. She's won numerous awards including the National Book Award and the Pulitzer Prize, and published more than 30 books, including a 'justice trilogy' of novels set on an Ojibwe reservation in North Dakota that may be most appealing to crime fiction fans.

THE ROUND HOUSE, the second in the loose trilogy, centres on Joe Coutts, a 13-year-old boy angered by the poor investigation into a brutal attack on his mother, who sets out to uncover the identity of his mother's attacker with the help of his best friends. Blending crime story and coming-of-age, the Sunday Telegraph said "Erdrich has achieved an impressive trick; a spellbinding read, an earnest message and fierce emotional punch".

|

| Marcie Rendon's second Cash Blackbear novel was shortlisted for an Edgar Award |

MARCIE R RENDON

Following David's recommendations back in September, I ordered novels from a few other Native American crime writers, including two mysteries by Marcie Rendon, a playwright, poet, author and activist who is a member of the White Earth Anishinabe Nation. I really enjoyed both books - MURDER ON THE RED RIVER and GIRL GONE MISSING - and in some great news they're now more widely available thanks to Soho Press, with more Cash Blackbear tales hopefully on the way in the not-too-distant future.

Set among the grain and sugar beet fields and small towns of North Dakota and Minnesota during the Vietnam War, the Cash Blackbear Mysteries centre on a tough young Ojibwe woman who’s survived tragedy and foster care and now drives truck, hustles at pool, and occasionally helps her only real friend Sheriff Wheaton solve crimes. I thought these were really good character-centric crime tales that also explore some of the prejudices and injustices faced by Native Americans.

|

| Most famous for his Arkady Renko |

MARTIN CRUZ SMITH

Perhaps the most renowned Native American crime writer is one that many may not know is Native American, especially given his seminal work is a series starring Russian investigator Arkady Renko, Yes, Martin Cruz Smith, author of the huge bestseller GORKY PARK, and the eight Renko novels that followed, is of Native American (Pueblo) descent. While GORKY PARK was a breakthrough novel for Cruz Smith in 1981, he'd actually published eighteen books the decade before that, ranging across pseudonyms and genres.

The film version of GORKY PARK went on to win an Edgar Award, but Cruz Smith himself had twice been an Edgar nominee for his earlier novels, including NIGHTWING (1977), a supernatural thriller inspired by the author's own tribal ancestry. Cruz Smith also co-wrote the screenplay of the 1979 film adapted from that novel, which did poorly on release but later developed a cult following.

|

| insert caption |

A native storyteller that I've been hearing a lot of great things about during the pandemic is Stephen Graham Jones, a Blackfeet author of experimental, horror, crime, and science fiction. I've recently bought THE ONLY GOOD INDIANS, his literary horror novel published in 2020 that was praised by NPR as also doing "a lot in terms of illuminating Native American life from the inside, offering insights into how old traditions and modern living collide in contemporary life".

Talking with Wanbli Weiden in September, he said of Jones: "He’s mainly known for his indigenous horror, but he wrote a [crime novel] that I think is almost a direct descendant of Louis Owens, called ALL THE BEAUTIFUL SINNERS. He very much takes Owens’ surrealistic style and then moves it in a new direction."

Thanks for reading. Until next time. Ka kite anō.

Whakataukī of the fortnight:

Inspired by Zoe and her 'word of the week', I'll be ending my fortnightly posts by sharing a whakataukī (Māori proverb), a pithy and poetic thought to mull on as we go through life.

Ehara taku toa, he takitahi, he toa takitini

(My success should not be bestowed onto me alone, as it was not individual success but success of a collective.)