I sometimes wonder what it would be like to have senses that

behave differently from those we actually have.

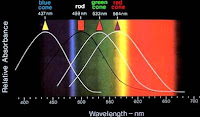

Not that I'm complaining; our senses are totally amazing as they are. But, for example, how does a dog see the

world when out for a walk? As she goes down the path, all her interest is in the smells. She's "reading the newspaper." She hardly bothers to look where she's going! Visually her world is in black and white because a dog’s eyes lack the cones that allow us

to split the light up into wavelength regions that our brains can interpret as

colors. Probably that’s so that she can see better in lower light than we can—an advantage for predators that may

be hunting at night.

But at the same

time, the dog is getting scent information much richer than ours. How does her brain integrate this information? As a ghostly shadow of the previous occupant

of that space? Or is it kept separate—rich

information about the past, but in no way confused with the present? I would guess the latter, yet I’ve seen dogs

shy from the smell of something dangerous as though the threat was still there.

For that matter, how do we know that we all

perceive colors the same way or even in a similar way? Yes, we will all agree that the wavelengths

around 550 nm are green (unless one of us suffers from some form of color blindness), but how can we tell if our perceptions

of green are the same. Maybe my green is your red?

Then, of course, there are lots of 'colors' out there that

we can’t see at all simply because our eyes are not sensitive outside the very narrow

wavelength range that we call “visible” light.

Probably that's because the range we can see is where the highest

amount of energy reaches the Earth through its atmosphere. It starts around 400 nm with the blue and

finishes around 650 nm in the red. The

shorter wavelengths start with the ultraviolet (much of which is filtered out

by the atmosphere fortunately) and the longer wavelengths are the infrared

running into the thermal.

There’s lots of useful information in what’s sometimes

called the near infrared - the wavelength range starting just after

red. For one thing, vegetation reflects

strongly in that region, pushing away the heat energy. This sudden jump in

reflectance is called the “red edge” and its strength and position can be used

to obtain indicators of plant health. For this reason, the satellites that supply

information for GoogleEarth, for example, actually measure the near infrared as

well. They take four simultaneous images

– one in the blue, one in the green, one in the red, and one in the infrared. This is no problem for most digital sensors

because they aren't as restricted in sensitivity as our eyes are. In fact, often digital cameras have filters

to block out the infrared because it can cloud or haze the image.

Here is a gray scale image of the infrared. White in these images will be vegetation, not snow.

|

Many photographers and artists have tried to show us the

world with other eyes by representing the infrared as one of the colors we

usually see. The results can be quite

amazing.

The image below was created by Irish photographer and artist Richard Mosse. It’s of Lac Vert in the Congo. Take a look at his powerfully dramatic images here.

|

| Lac Vert in the Congo by Richard Mosse |

And sometimes we can see a lot more interesting detail if we

look with other eyes, such as this galaxy example.

Once you get to the longer wavelengths, you get into the

thermal range and now it's not the reflection of the light that is

interesting, but rather the emission of the light from the item. Really what is

happening is that we are translating the different temperatures to different

colors with red usually representing the hottest and blue the coolest.

Of course, all of these images are, in the end, just

representations of these other light ranges as the colors we're used to

seeing every day. We can’t really see

them as part of our world with our eyes any more than we can visualize the

history of a path with our noses.

Of course, all of these images are, in the end, just

representations of these other light ranges as the colors we're used to

seeing every day. We can’t really see

them as part of our world with our eyes any more than we can visualize the

history of a path with our noses.

Michael - Thursday

And that's just vision. I think If I had the scenting ability of a dog I would go crazy. Or just throw up a lot.

ReplyDeleteI thought some bright spark had now discovered dogs can see in colour. They can certainly tell brown ( chocolate) from orange ( the medication hidden in the chocolate). And they (well some breeds) have a visual focus that sees movement to the exclusion of all else. My other half has this also- when my hand goes near a credit card....

ReplyDeleteAll I want is the eyes of an eagle - resolution is about five times better than ours. The size is about right, so we could fit them without too much hassle. Imagine being able to see an ant from the top of a 10-story building! Or a rabbit from two miles!

ReplyDeleteComing to think of it, why would I imagine those things? But I'd certainly like to do them.

Stan, think what the bugs in the carpet would look like? You'd spend your life hoovering!

ReplyDeleteDon't you and Stan realize that mothers already have those eye?. At least mine did...every time I did something wrong. Yes EvKa, she was a very busy woman.

DeleteI have NO desire for an enhanced sense of smell. I'm already terrified of going to public gatherings for fear of being gassed by perfumes, colognes, hair shampoos and treatments... shudder.

ReplyDeleteAnd, Jeff... there was NEVER any doubt. Not only a busy woman, but also a saint.

Caro is right (as usual). The issue with dogs is that they have two types of cones - not three, as we have. This gives them a limited discrimination of hues. Interesting article on the topic at: http://www.smithsonianmag.com/science-nature/new-study-shows-that-dogs-use-color-vision-after-all-13168563/?no-ist

ReplyDeleteThanks Caro!

I remember reading that the mantis shrimp sees far more colors and spectra than human eyes can see, and wondering what the world must look like through their odd, alien eyes. It's fascinating to consider how the other inhabitants of our planet see it!

ReplyDelete