Annamaria on Monday

On my recent trip to Kenya, I had my heart set on my first visit to Kenya's first colonial capital:Mombasa, which had been famous since the Middle Ages. Alas, the advice my fellow travelers and I received was "Now is not the time." Radicals, evidently, are attacking their fellow Kenyans. My fellow travelers and I opted for the nearest historic port city, Zanzibar. Boohoo.

Mombasa is the setting for the second in my Africa series, which is just now enjoying the release of a new and beautiful edition. My planned visit would have been my first opportunity to see the legendary city in person, since when I was working on that story, my life circumstances did not allow for such travel. How I wish that today I could have my own firsthand description and photos to share with you. But failing that, here is a glance at a factual (as opposed to my fictional) portrayal of the background town of Vera & Tolliver #2,

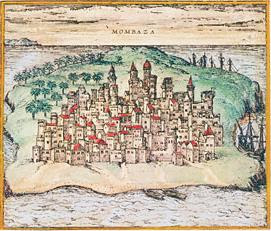

Quite a few cities on our sacred planet have become important because of their location: on an important coast with a natural, deep-river port. Siracusa in Sicily, Cape Town. New Orleans, and New York leap immediately to mind. Mombasa - on the Indian Ocean, became such a center of trade sometime around 900 A.D. That trading village had early contacts with India and China and over the centuries grew, into the largest port on the east coast of Africa. with a current population of more than 1.2 million and the metropolitan region of 3.5 million.

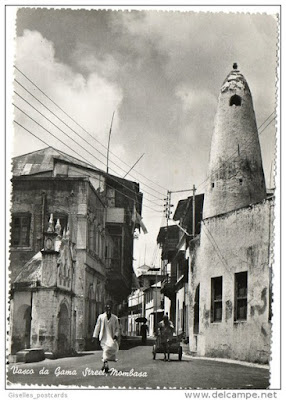

The Portuguese arrived in the 16th Century, most famously led by the first European on the scene: Vasco da Gama in 1498. Not finding an easy welcome, he eventually built Fort Jesus (a historic venue that appears often in my 1912 story).

After the uneasy and intermittently violent occupation by the Portuguese, next came a 1585 takeover by the Ottomans. Mombasa's culture and language became predominantly Swahili. Eventually, in the 18th Century, independent Sultans took charge, interrupted by a couple of years of British governance.

The British East Africa Association moved in on 25 May 1887 and came to stay. Though the Sultan of Zanzibar retained a ten mile swath of the coast, including Mombasa, in exchange for a monetary tributes, he made the British Mombasa's governors. The Brits went on to build the "Lunatic Express" railroad that you read about here a couple of week ago, and for a few years Mombasa was the capital of the Protectorate of British East Africa.

Mombasa continued to be largely a diverse but mostly a Muslim city, where Swahili was the local language. (It is now the official language of Kenya.). Regardless of who was in charge, trade in Mombasa at the time was mostly in gold, ivory, sesame, millet, and coconuts. Nowadays, it is mostly coffee, tea, and food grown in the highlands and shipped to supermarkets in Great Britain.

Kenya became an official colony of Great Britain in 1920. From 1952 till 1960, all of Kenya suffered though the Mau Mau Rebellion or Kenya Emergency - A brutal battle on both sides. Finally, on the 12 December 1963 Kenya achieved independence.

Just three months before my failed February trip, King Charles III visited Kenya and Mombasa. Perhaps if it was good enough for His Majesty it might have been good enough for me and my friends. On the other hand, I would imagine the royal Brit had a better security detail than my friends and I could have mustered. The local newpaper said, "The region has seen an increase in radicalization and militants kidnapping, or killing Kenyans."

I guess it is best we did not chance making that visit. Mombasa has been there for 1124 years. And Fort Jesus, the place I most wanted to see in person, has survived for 518. There is hope that they will be there if I ever get a chance to try again. In the meanwhile readers of The Idol of Mombasa can make the trip in my time machine. And despite the murders in my story, nothing bad will happen to them when they take their imaginations to the exotic Kenya coast.