Annamaria on Monday

In 1540, when the Spanish Conquistadores waltzed into what is now northeastern Arizona and Northwestern New Mexico, there were around 44 thousand Pueblo Indians living there in peace and in harmony with their environment. They lived in scores of settlements densely built on high cliffs overlooking some of the most marvelous landscape on the globe.

The arrival of soldiers, missionaries, and settlers ended that peaceful way of life. Within a year, Francisco Vasquez de Coronado was warring against the Pueblo people. In 1598, a certain Juan de Onate arrived with more than a hundred soldiers, ten Franciscan priests, and settler families along with their servants and slaves. When the Native Americans rose up to show their displeasure at the invasion, Onate massacred and enslaved hundreds. And to make sure no such effrontery ensued, he ordered his troops to cut off the foot of any man 25 or older. After that the fertile farmlands of the Pueblo towns were taken over by the Spanish settlers.

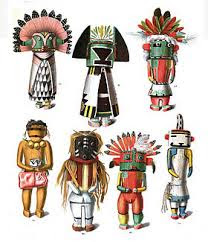

The priests went to work on Kachina—the local religion. They banned all of the Native ceremonies, which involved ingesting special mushrooms and other substances, wearing masks (!), dancing, chanting, and—with effigies—invoking intercession of intermediaries between the earthly people and God. When the religious persecution turned brutal, Spanish Officials intervened on the behalf of the Native People, trying to stop the worst of the atrocities. For their trouble the Spanish officials found themselves brought up before and tried by that greatest ever technique for subjugation—the Inquisition.

Eventually, in 1675, the Spanish Governor Juan Francisco Trevino ordered that forty-seven tribal medicine men be arrested as sorcerers. Four received the death penalty. Another four were publicly put to the lash and then imprisoned. Eventually Trevino was forced to release the prisoners.

Among those let go was Po’ Pay (This is only one of the many ways his name is spelled). Once he left the dungeon, Po’ Pay spent the next four years working on his plan to evict the Spanish. To make his rebellion work, he had to accomplish something never done in that place before, in fact, something against the culture of the Pueblo People—he had to convince the people from forty-six settlements to fight together. He managed to get their agreement. Po’ Pay invented an ingenious way for the groups—from as far as 200 miles away—to converge. He set the date for 11 August 1680. To get the far-flung warriors who didn’t have calendars to show up on time, he sent runners to each Pueblo with ropes with a number of knots. They were to untie a knot at dawn each morning. The morning they untied the last knot they went on the attack.

They turned out in such numbers that they overwhelmed the invaders. They killed 400 Spaniards and destroyed most of their settlements. They put Santa Fe under siege and cut off their water. The Governor of New Mexico had barricaded himself in his palace. On 21 August, he and his men broke out, killed as many Pueblo man as they could, and high tailed it out of the country.

Po’ Pay and his closest Puebloan lieutenants set out destroy all traces of the Spaniards. Many myths exist about what happened next. Here is what we are pretty sure of: Po’ Pay, perhaps because he thought his religion wanted him to, went about urging the people in the various settlements to return their land and their lives to the way it was a hundred and forty years before. That meant not only getting rid of the churches, the crosses, the Spanish fruit trees, and farm animals. They were also to go back to having only Puebloan names, take ritual baths to cleanse their bodies as well as their souls, and—if they had married women in the Catholic church, to renounce their wives and take new ones according to the old traditions.

The Pueblo culture had never called for a single leader for all the settlements. The strictures Po’ Pay insisted upon chafed, and the paradise he promised if the Spanish where expelled did not come to pass. His leadership lasted only a year.

Life without the Spanish went on for only twelve years. In 1692, Diego de Vargas returned and reconquered the territory. When, in 1696, the Puebloans attempted another uprising, his punishment was merciless. But Po’ Pay’s revolt had some lasting benefits. The colonial Spaniards allowed the Native People more land and the right to practice their old religion.

Today’s post is inspired by my first in-person museum visit since February. With all the necessary precautions, my friend Rosemary took me to an exhibit at the Montclair, New Jersey Museum of Art. One of the exhibitions was of works by Virgil Ortiz, a Puebloan artist, son of a renowned family of potters. His works, inspired by the Po’ Pay Rebellion combine the Native art of pottery with themes commemorating Po’ Pay. I loved them.

AS a boss of mine once said "People are no damned good!" Ortiz's work is gorgeous.

ReplyDeleteYou know, Stan--I think most people are good. But I profoundly agree if we say Empire builders are no damn good! I wish you could have seen Ortiz's works in person. I wanted take one home. But it would have been hard to choose. He also has written a dystopian sci-fi graphic novel of the Po' Pay story in 2180, with a female protagonist. He has designed clothes too. Next thing we know he'll be writing music!!!

ReplyDeleteGo, Virgil Ortiz, go. What beautiful pottery designs. Love them.

ReplyDeleteThanks for posting this.

About the horrible history of the Spanish invaders, I say thanks for telling the Pueblo people's history and Po'Pay. Did not know this.

Kathy, Like you, I was completely unaware of this, even though I have written books about Spanish colonialism. I highly recommend a gander at Virgil Ortiz's works on his website. He is a wonderman.

ReplyDeleteFunny, sis, how your post put me back into grade school history class. I vividly remember thinking as we learned about the Spanish in the New World, how utterly brutal they were. There seems little argument in their defense, but over the years I came to wonder why Spanish conquerers were portrayed that way, while (other) European conquers largely escaped such universal critical condemnation. I came to realize it would have been a different educational experience had the texts been written in Spanish, or a native American language.

ReplyDeleteRight you are, Bro. The English-speaking people who subjugated the local peoples were just as brutal, but the history books we read as kids were written by English-speaking historians. Colonialism was the scourge of the earth, and we are bearing its bitter fruit still—worldwide.

Delete