|

| Rishi Reddi |

I recently read an incredible novel: PASSAGE WEST by Rishi Reddi. I fell hard for the small cast of sympathetic characters, Indian and Mexican immigrants in early 20th century America, and I yearned to know more from her about this mysterious part of American history. I’m sharing an interview that took place in a series of emails. Join me as I learn more about the history of Indian activism and the great sacrifices of early Punjabi immigrants to California.

Rishi, welcome to Murder is Everywhere, a blog that highlights the very best crime writing set in locations worldwide. The first thing I want to ask is about the origination of your idea to set PASSAGE WEST in California’s Imperial Valley.

While taking a law school class about U.S. immigration, I learned that, during the 1920s, certain applicants’ racial classification as “white” was a pre-requisite for a path to citizenship. I grew very interested in a case called United States v. Thind. Mr. Thind was a Punjabi-born United States Army veteran who had gained his U.S. citizenship based on his military service. He was later stripped of his citizenship by the U.S. Supreme Court, which reasoned that although he was Caucasian, he was not considered “white” under popular belief and therefore his citizenship had been improperly granted. I was fascinated by the racial aspects of the court’s decision and also the fact that South Asians had immigrated to America so early -- at the turn of the 20th century. I didn’t understand how much those early South Asians had contributed to American society. The population was mostly comprised of men living in bachelor-like conditions, trying to make a life for themselves in very isolating circumstances. Many who had settled in rural California found sweethearts among the Mexican population and earned reputations as very good farmers. They made friends among other immigrant groups and also earned the respect of American business associates. This was the real-life multi-cultural historical community I wanted to write about.

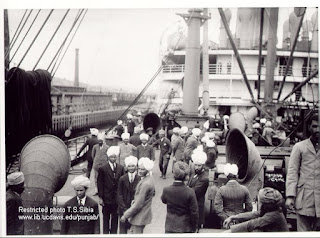

|

| SS Minnesota, Seattle June 23, 1913, courtesy WA State Historical Society |

From what I’ve read about the current situation in the Imperial Valley, a high number of its residents live in poverty and have limited access to health care. A few massive agri-business companies are the chief employers in this area north of Baja California, with Arizona on its eastern border. How did the location fit into the crimes you write about in your novel?

The crime is based on a true event. It is horrific but also understandable in some way. The act committed by one of the protagonists was sparked by how farming immigrants were being treated in the 1920s; how these families worked to develop agriculture in the Imperial Valley, yet were ultimately robbed of the profits of that hard work. The story is set in this specific time and place, but portrays nationwide social dynamics. I meant it to be a story about America itself.

How common was it for Asian immigrants to find themselves in “unsettled” parts of the United States?

It was very common! These “unsettled” areas allowed immigrants a certain amount of social freedom, away from the cultural constraints of mainstream, conventional American society. They were wanted and needed in areas where many privileged folks did not care to go. In Imperial Valley, many immigrants stayed through the severe heat of the summer in order to earn a livelihood, but many non-immigrant whites could leave during those months, even if they were not particularly privileged, to find work in cities and other more populated areas without the fear of being driven out through violent mobs or other ways.

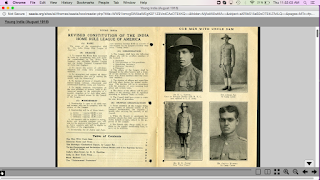

|

| Mexican gang labor in1930s, by Dorothea Lange, courtesy Library of Congress |

One of the most startling things for me was the redefinition of race by the US government for Indian immigrants. What were the things they could—and could not do—because of laws based on national origin and color?

It was tricky to untangle all the ways that the Supreme Court rulings in those years defined the term “white,” and the way that the designation, while interacting with federal, state, and local laws, affected their lives. In the novel, I reference the Thind case, which established a racial classification for South Asians. Because Thind was classified as neither “white” nor “black,” he was deemed to be of a race that was ineligible for U.S. citizenship. That happened under federal law. And, under California’s state law, people who belonged to a race that was ineligible for U.S. citizenship could not own land or enter into long-term leases to farm any land. So, the federal and state laws worked together to prevent the Punjabi immigrants from farming for their livelihood, even if they had been doing so for many years. That situation provided the central plot issue for Passage West. Also, under the state miscegenation laws, people of differing races could not intermarry. This law was not uniformly enforced, which is why Karak and others were able to find wives in the United States, but technically, what he did was illegal. At that time in California, if the clerk of their county refused them a marriage license, many “inter-racial” couples would cross the state border to marry in other states.

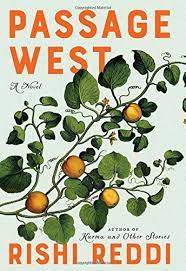

|

| Closeup of Young India story about Indian-American soldiers in WWI |

What additional research did you do for the novel? How much of it is based on actual events?

I had not set out to write a huge novel. I was hoping for a smaller book dominated by a love triangle between an immigrant farmer named Ram Singh, a daring Mexican woman named Adela, and Ram’s devoted wife Padma, whom he was forced to leave behind in Punjab. But after I researched the topic more deeply and interviewed the descendants of early South Asian immigrants to California, I realized I had a much larger story to tell.

I got lost in the research! I discovered the South Asian men who fought for the United States in World War I, and also learned about covert US-based plots to overthrow the British in India. The vast majority of the novel is founded on actual events that I learned about from the children of that community or that I read about in newspaper articles from the 1920s or from reading modern sociological studies. The research was so fascinating that it was hard to decide which story to tell. Basically – I decided to include all of it.

I smile when you mention “covert US-based plots to overthrow the British in India” because that turns up in my 2021 novel, THE BOMBAY PRINCE. Can you tell me more about the Ghadar Party?

Many Indian intellectuals, revolutionaries and laborers who were working for the overthrow of the British in India settled in the United States, a place where they could continue their organizational activities outside of British scrutiny. Despite their efforts, they attracted the attention of the United States government, which had been heavily lobbied by the British to curtail their efforts. The Indian revolutionaries drew upon the ideological roots of America, Thomas Jefferson and Patrick Henry among others, in their efforts to draw people to their cause. They led a movement called Ghadar, meaning ‘Revolution,’ and published a globally-distributed newspaper under the same name. Although they may have been unsuccessful in their immediate efforts, their ideology certainly pushed the Subcontinent toward independence two decades later.

What else did researching for PASSAGE WEST reveal about the history of the United States?

I am fascinated by how many people were written out of the history books. My research took me to old newspaper accounts and government studies about immigrant communities in the United States in the first quarter of the 1900s. Newspaper journalism is often called “the first draft of history,” however, when we study that history in school, it is in the form of a highly edited subsequent draft that excludes so many that lived and worked in this country. Unfortunately, it is the edited draft of history that has formed our American Narrative, and it is inaccurate.

The novel’s first chapter opens with the protagonist Ram Singh, in his elder years, taking possession of a dead man’s document, and remembering something of a past crime. Ultimately, you narrate the long road toward a killing and a complicated, twist-filled murder trial. Had you thought of your novel fitting into a crime fiction genre, and would you have crime in future writing?

I did not think of this novel as fitting into the crime genre while I was writing. It was only after the book was out in the world that I read a very flattering review by Doreen Sheridan on the website “Criminal Element,” and I thought – yes – the novel could be seen in this light, too. The crime that lies at the center of the novel was based on a real multiple homicide, so I don’t know why I never thought of that angle before. And as a lawyer, I just couldn’t keep myself away from a good old-fashioned courtroom scene, where something crucial is revealed! It was certainly fun to write. If I thought in terms of genre at all, I was thinking of a classic Western…. A gun, a horse, a wind-blown landscape….

You and I have similar family journeys from India, to Britain, and then finally the US. Do you feel viewed as a Westerner at times in India, or are you welcomed as a home comer? How did your diaspora upbringing affect research for this book when you went to Punjab?

I have always felt that I did not wholly belong to either place: India or the United States. Part of that is because when I was growing up in America in the 1970s and 1980s, India and America were very far apart culturally and politically. Years later, when I was in India for a couple of readings for my first book, Karma and Other Stories, I realized that I was being viewed essentially as a foreigner author. I had always been aware of this “foreignness” in my many childhood trips there, but it was ironic – given that the book was about trying to remain “Indian” while living in the US! It was even more interesting to go to Punjab for my research for Passage West. In Punjab, I was seen as an American, but I was also seen as Telugu, not Punjabi. I certainly don’t speak Punjabi, and the customs and culture of north and south India, where I was born, can be very different.

Was this your first novel, or is there another novel in the drawer?

I do have another novel “in the drawer” from a long time ago -- don’t we all? It will never see the light of day. I managed to create a few good scenes – and I sure learned a lot writing it.

I am grateful to Rishi for honoring a community that's been largely forgotten. PASSAGE WEST, selected by the LA Times as one of The Best of California Books of 2020, is a must for anyone interested in South Asian crime fiction, historical mysteries, and immigration stories. Find out more about Rishi, including her availability for book club conversations, at her website rishireddi.com.

Thank you for this fascinating story. In South Africa, we tend to think that the reason South African race discrimination was worse than in many other countries was because it was institutionalized in law. But it seems the US was just as overt even post slavery. I look forward to learning more in Passage West.

ReplyDeleteFascinating. Thanks for the interview, Sujata and Rishi!

ReplyDeleteThe U.S. has a history of such racism against so many peoples and nationalities, starting with Indigenous peoples who got here first and whose land was taken.

ReplyDeleteBut I didn't know this history and I look forward to reading this book.

I found the interview fascinating in no small part because of my family's links to Imperial Valley growers. I can't wait to read "Passage West."

ReplyDelete