The Murder of Robert and Jeanne Smit: An apartheid-era killing

| The evening of 22 November 1977 was a fateful one for prominent political South African couple Robert Van Schalkwyk Smit and wife Jeanne-Cora. They were both shot and stabbed to death in their home that night but at different points in time. Jeanne was the first victim as she waited for husband to return home from work, and the same horrific end awaited him when he later arrived and opened the front door of the house. |

Who were the Smits?

Robert Smit was a member of South Africa’s National Party (NP), an Afrikaner party that existed from 1914 to 1997. Afrikaners are descended from South African’s Dutch settlers of the 17th and 18th century. The NP promoted Afrikaner economic interests and the severance of South Africa’s ties to the United Kingdom. Rising to prominence in 1948, the party was responsible for enforcing the vicious policy of racial segregation, apartheid, which gave rise to one of the greatest resistance movements of all time. Smit himself was the managing director of Santam, South Africa's largest short-term insurance company and one that the government used to circumvent sanctions waged against the country's procurement of military and economic resources.

|

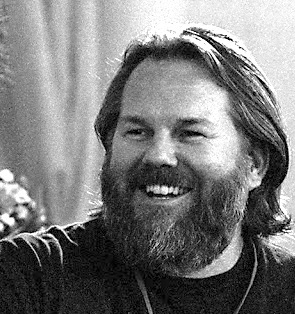

| Figure 1: Robert Smit Robert Smit (Photo: flatnote.co.za/foto24) |

Dr. Smit was a privileged Rhodes scholar who attended Pembroke College, Oxford, and Stellenbosch University, where his thesis was “South Africa and International Trade Politics.” Liza Smit states in her book that her father felt it was wrong that people of color did not have the right to vote. Apart from that, Liza doesn’t appear to further characterize how her father felt about apartheid as a system of oppression. From 1971 to 1975, Robert was South Africa’s ambassador to the IMF and the Smit family lived in Washington, D.C.

Jeanne-Cora, who didn’t like the “Cora” part of her name, married Robert in 1958 while he was at Oxford. Liza relates that her mother Jeanne was a rock and an anchor for Robert, often spurring him on and encouraging him when he needed fortitude. By all accounts, she was a devoted wife and mother who played the major role in bringing up her two children Liza and Robert, Jr. She enjoyed painting and pottery.

What happened that fateful night?

Robert Smit was running for National Party candidate in the Springs constituency. Elections were to be held on November 30, 1977. Robert and Liza had rented a house in Springs, while their children stayed home in Pretoria, South Africa’s capital.

On November 22, a Tuesday, Robert was at his Springs election offices. Jeanne was out during the afternoon, but the Smits’ driver, Daniel, took her back home around 6:10 PM. Daniel testified later that he had left Mrs. Smit at 6:50 PM. It appears that Robert had made arrangements to speak to some anti-National Party voters at his home, and at either 7:14 or 7:40 (accounts differed), Jeanne called Robert’s office assistant to ask her to inform Robert that “his 'guests' are waiting for him.”

It seems clear that as Jeanne hung up the phone, she turned to find a gun pointed at her head and defensively raised her left hand seconds before the first shot. She was found slumped over the phone and autopsy showed she had been shot in the head, hand, and back. Additionally she was stabbed 14 times post mortem with a weapon consistent with a stiletto knife. The murder demonstrated “overkill,” i.e. more violence than absolutely necessary to effect the victim’s death, indicating perhaps underlying personal feelings of rage on the murderer’s part.

On November 22, a Tuesday, Robert was at his Springs election offices. Jeanne was out during the afternoon, but the Smits’ driver, Daniel, took her back home around 6:10 PM. Daniel testified later that he had left Mrs. Smit at 6:50 PM. It appears that Robert had made arrangements to speak to some anti-National Party voters at his home, and at either 7:14 or 7:40 (accounts differed), Jeanne called Robert’s office assistant to ask her to inform Robert that “his 'guests' are waiting for him.”

It seems clear that as Jeanne hung up the phone, she turned to find a gun pointed at her head and defensively raised her left hand seconds before the first shot. She was found slumped over the phone and autopsy showed she had been shot in the head, hand, and back. Additionally she was stabbed 14 times post mortem with a weapon consistent with a stiletto knife. The murder demonstrated “overkill,” i.e. more violence than absolutely necessary to effect the victim’s death, indicating perhaps underlying personal feelings of rage on the murderer’s part.

Jeanne appeared to have been killed 30 minutes to three hours before Robert came home. As he entered the lobby, the killer(s) fired one shot, which glanced off Robert’s neck and lodged in the wall, a second one to the chest at close range, and one to the back of the head. Lastly, he was stabbed in the back once, apparently with the same stiletto. Two different types of guns were used, according to the police, suggesting two assailants, at least. Although bloody drag marks and shoe prints in Figure 2 above are apparent, there's little or no further information, e.g., where did the Smits' bodies lie, exactly? Clearly, this picture was taken some time after the bodies were removed. At any rate, if the photo is supposed to demonstrate how the police handled the crime scene, it's obvious from the modern forensic perspective how many egregious errors are being committed, e.g. the wearing of regular street clothes, failure to secure the area, and trampling all over the crime scene. And don't ask me to explain the apparently clueless guy in shorts and what in the world he's doing there. Or is he the murderer returning to the scene of the crime? Just a passing thought.

The Smits’ bodies were not discovered until early the following morning when Daniel, their driver, came in for work. Spray-painted on the kitchen wall and cabinets were the strange words “RAU TEM.” More on that later.

|

| Figure 3: The words "RAU TEM" sprayed in red paint |

|

| Figure 4: Investigators at the home of Robert Smit, 2 November 1977 |

The Suspects

A political motive has long been thought the most likely in the Smit murders. The scrawled words "RAU TEM" turned out to be Afrikaans for a specialist sub-unit of the notorious intelligence agency Bureau of State Security (BOSS), and many thought it was its murderous commander, Hendrik van den Bergh, (also called "The Tall Assassin") who ordered the hit. However, that's questionable, because not only was the spray painting not a typical MO of a BOSS assassination, the can of paint used actually belonged to the Smits--i.e. it was already there in the kitchen when the murder took place and was therefore unlikely to have been part of the plan. Compared to the MO of the murder itself, it seems impulsive and unplanned. A key question is, who were the "guests" at the Smits' home? Were they really who they said they were?

At that time in South Africa's political history, the atmosphere was fraught. During this period, the country was in utter turmoil. The inquest into the death of Steve Biko had begun on November 14, a black high school student Sipho Malaza had allegedly died in police custody, the twenty-first in some 20 months, and embargoes against South Africa were beginning to mount. Against this backdrop, it's easy to see how all kinds of people in various political camps could have ended up dead. The Information Scandal also broke around that time, costing the jobs of the prime minister and a couple of his cabinet members. The scheme deflected funds from the defense budget to a number of pro-apartheid propaganda campaigns. Robert Smit might have had detailed detrimental information that he intended to expose after his putative election--a threat that would have been too dangerous for the implicated persons to let stand. Other conspiracy theories, too detailed to go into here, included Israel and nuclear secrets.

I find the absence of the mention of the bloody apartheid struggles in Liza Smit's book both striking and odd, but it may reflect how sheltered, privileged, and possibly oblivious, her life was. However, she recounts a story that is perhaps revelatory of the kinds of sensitivities, or lack thereof, during that murderous era. Two days after the killings, she and her brother were brought to the Springs home (the children had been staying in Pretoria when the murder took place) and shown the scene of the crime in a matter-of-fact way. The bodies had been removed, but the spattered, dried, and clotted blood was still there in all its gruesome glory. The policeman at the scene explained to Liza (remember she was only 13), "Here is where your father was shot, here is where he fell, and here are the marks where he was dragged down the passage." I can think of nothing more cruel than depicting the Smits' murder to their child in this uncaring fashion.

Summary

The savage killing of Robert and Jeanne Smit occurred in an equally brutal socio-political climate in which violence and cruelty were almost the norm. Unsolved till this day, the chances that it will ever be anything but a cold case are slim to none.

By Kwei Quartey

By Kwei Quartey

Thanks, Kwei. Very interesting, very sad. Murder, like war, is politics by other methods.

ReplyDeleteDreadful, Kwei. I cannot help adding that for me November 22 is a day of sadness for another reason. The murders you describe here took place on the 14th anniversary of the assassination of John F. Kennedy - another murder many believe has never been sufficiently explained.

ReplyDeleteThe treatment of the Smit children is completely incomprehensible. One might posit many motives for the murders. I defy anyone to come up with a plausible explanation for treating bereft children in such a brutal way.

Very interesting. I remember reading about this even though I was then studying in the USA. The daughter's comment about her father being against discrimination reminds me of how many Whites today relate how they were against apartheid in the old NP days. My guess about the man in shorts is that he was a detective. As to the killers, it could be people on either side of the political spectrum, although the brutality of the attacks suggest to me that they were part of the establishment. My encounters with the police and Special Branch about ten years earlier were always far from pleasant.

ReplyDeleteWhy do I sense there's a kernel of a bust-out story taking root in some Africa-appreciative author's mind at this very moment!

ReplyDeleteI was living in Johannesburg at the time, and remember that this was a very big deal indeed. However, there was little attempt to blame it on "terrorist" activities, which suggests to me that Stan's explanation may be right. That leaves the question as to why...

ReplyDelete