Today is Father’s Day, something that originated in the United States in the early years of the last century. It seems that two women independently came up with the idea. One was Grace Golden Clayton, in Fairmont, West Virginia, who suggested such a day in 1908, to honour 361 men killed in a mine explosion. In Spokane, Washington, on June 19thtwo years later, a woman called Sonora Smart Dodd celebrated her father, a Civil War veteran called William Smart, who had raised six children after his wife died in childbirth. Ms Dodd felt that it was time fathers were as equally acclaimed as mothers.

|

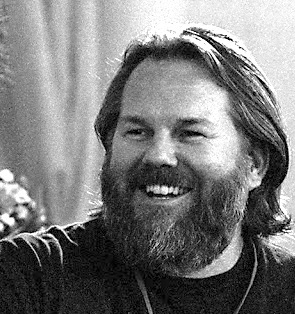

| William Jackson Smart, in whose honour the first Father's Day was held |

Lobbying for the third Sunday in June to be made a national holiday started up almost immediately, and in 1924 President Calvin Coolidge recommended such action was taken. However, it wasn’t until Lyndon B Johnson signed an executive order in 1966 that the date was designated, and not until 1972, under Nixon, that the date was officially recognised.

Father’s Day has since been taken up around the world, although the date varies enormously, with Iran using March 14th, and Thailand December 5th.

Although the holiday has now become incredibly commercialised, I confess to always trying hard to find suitable gifts for my father, and what better pressie than books? I know in Iceland there is such a precedent at Christmas, where they have the Jólabókaflóð which means the Christmas book flood. The idea is that you gift books on Christmas Eve, and the remainder of the night is spent reading.

Well, I think I may have caused a minor book flood at my parents’ house during this last week, as my Father’s Day selections arrived. My father, having no sense of occasion, didn’t even wait until Saturday night before he began tucking in.

|

| A man reading. ( Not my father.) |

He’s not easy to buy books for, as he’s not really a reader of fiction, preferring interesting non-fiction instead.

Getting recommendations for just the right kind of books is always tricky. He likes biographies, providing they have a scientific or medical slant. He does not follow any sport except Formula One, and comments that in recent years this once hair-raising spectacle has become somewhat processional

|

| The Monaco Grand Prix just wasn't the same after the introduction of the new safety regulations... |

For Father’s Day this year, the first one I found for him was Radical Technologies: The Design of Everyday Life by Adam Greenfield. ‘Everywhere we turn, a startling new device promises to transfigure our lives. But at what cost? In this urgent and revelatory excavation of our Information Age, leading technology thinker Adam Greenfield forces us to reconsider our relationship with the networked objects, services and spaces that define us. It is time to reevaluate the Silicon Valley consensus determining the future. Having successfully colonised everyday life, radical technologies—from smartphones, blockchain, augmented-reality interfaces and virtual assistants to 3D printing, autonomous delivery drones and self-driving cars—are now conditioning the choices available to us in the years to come. How do they work? What challenges do they present to us, as individuals and societies? Who benefits from their adoption? In answering these questions, Greenfield's timely guide clarifies the scale and nature of the crisis we now confront—and offers ways to reclaim our stake in the future.’

The second one was The Infinite Monkey Cage—How to Build a Universe by Prof Brian Cox, Robin Ince, and Alexandra Feacham. ‘Professor Brian Cox and Robin Ince muse on multifaceted subjects involved in building a universe, with pearls of wisdom from leading scientists and comedians peppered throughout. Covering billions of concepts and conundrums, they tackle everything from the Big Bang to parallel universes, fierce creatures to extra-terrestrial life, brain science to artificial intelligence. How to Build a Universe is an illuminating and inspirational celebration of science—sometimes silly, sometimes astounding and very occasionally facetious.’

Next up was The Science of Everyday Life: Why Teapots Dribble, Toast Burns and Light Bulbs Shine by Marty Jopson. ‘Have you ever wondered why ice floats, how the GPS on your mobile phone works (and what it has to do with Einstein), or why woollen jumpers shrink in the wash? In this fascinating scientific tour of household objects, The One Show's resident scientist Marty Jopson explains the answers to all of these, and many more, baffling questions about the chemistry and physics of the stuff we use every day. Always entertaining and with no special prior scientific knowledge required, this is the perfect book for anyone curious about the science that surrounds us.’

And finally, Do No Harm: Stories of Life, Death and Brain Surgery by Henry Marsh. ‘What is it like to be a brain surgeon? How does it feel to hold someone's life in your hands, to cut through the stuff that creates thought, feeling and reason? How do you live with the consequences when it all goes wrong? Do No Harmoffers an unforgettable insight into the highs and lows of a life dedicated to operating on the human brain, in all its exquisite complexity. With astonishing candour and compassion, Henry Marsh reveals the exhilarating drama of surgery, the chaos and confusion of a busy modern hospital, and above all the need for hope when faced with life's most agonising decisions.’

In a similar vein, I recently sent him a copy of Accidental Medical Discoveries: How Tenacity and Pure Dumb Luck Changed the World by Robert W Winters. ‘Many of the world’s most important and life-saving devices and techniques were often discovered purely by accident. Serendipity, timing, and luck played a part in the discovery of unintentional cures and breakthroughs: A plastic shard in an RAF pilot’s eye leads to the use of plastic for the implantable lens. The inability to remove a titanium chamber from rabbit’s bone leads to dental implants. Viagra was discovered by a group of chemists, working in the lab to find a new drug to alleviate the pain of angina pectoris. A stretch of five weeks of unusually warm weather in 1928 played a role in assisting Dr. Alexander Fleming in his analysis of bacterial growth and the discovery of penicillin. After studying the effects of the venom injected by the bite of a deadly pit viper snake, chemists developed a ground-breaking drug that works to control blood pressure. Accidental Medical Discoveries is an entertaining and enlightening look at the creation of 25 medical inventions that have changed the world—unintentionally. The book is presented in a lively and engaging way, and will appeal to a wide variety of readers, from history buffs to trivia fanatics to those in the medical profession.’

Earlier still, on the recommendation of FaceBook friends, I got him Cod: A Biography of the Fish That Changed the World, by Mark Kurlansky. ‘The Cod. Wars have been fought over it, revolutions have been triggered by it, national diets have been based on it, economies and livelihoods have depended on it. To the millions it has sustained, it has been a treasure more precious that gold. This book spans 1,000 years and four continents. From the Vikings to Clarence Birdseye, Mark Kurlansky introduces the explorers, merchants, writers, chefs and fisherman, whose lives have been interwoven with this prolific fish. He chronicles the cod wars of the 16th and 20th centuries. He blends in recipes and lore from the Middle Ages to the present. In a story that brings world history and human passions into captivating focus, he shows how the most profitable fish in history is today faced with extinction.’

Another such recommendation was The Moth: This Is a True Story by Catherine Burns and The Moth Group, with an introduction by Neil Gaiman. ‘Before television and radio, before penny paperbacks and mass literacy, people would gather on porches, on the steps outside their homes, and tell stories. The storytellers knew their craft and bewitched listeners would sit and listen long into the night as moths flitted around overhead. The Moth is a non-profit group that is trying to recapture this lost art, helping storytellers—old hands and novices alike—hone their stories before playing to packed crowds at sold-out live events. The very best of these stories are collected here: whether it's Bill Clinton's hell-raising press secretary or a leading geneticist with a family secret; a doctor whisked away by nuns to Mother Teresa's bedside or a film director saving her father's Chinatown store from money-grabbing developers; the Sultan of Brunei's concubine or a friend of Hemingway's who accidentally talks himself into a role as a substitute bullfighter, these eccentric, pitch-perfect stories—all, amazingly, true—range from the poignant to the downright hilarious.’

And lastly, Elephant Company: The Inspiring Story of an Unlikely Hero and the Animals Who Helped Him Save Lives in World War II, by Vicki Croke. ‘Billy Williams came to colonial Burma in 1920, fresh from service in World War I, to a job as a "forest man" for a British teak company. Mesmerized by the intelligence, character, and even humor of the great animals who hauled logs through the remote jungles, he became a gifted "elephant wallah." Increasingly skilled at treating their illnesses and injuries, he also championed more humane treatment for them, even establishing an elephant "school" and "hospital." In return, he said, the elephants made him a better man. The friendship of one magnificent tusker in particular, Bandoola, would be revelatory. In Elephant Company, Vicki Constantine Croke chronicles Williams's growing love for elephants as the animals provide him lessons in courage, trust, and gratitude. But Elephant Company is also a tale of war and daring. When Imperial Japanese forces invaded Burma in 1942, Williams joined the elite Force 136, the British dirty tricks department, operating behind enemy lines. His war elephants would carry supplies, build bridges, and transport the sick and elderly over treacherous mountain terrain. Now well versed in the ways of the jungle, an older, wiser Williams even added to his stable by smuggling more elephants out of Japanese-held territory. As the occupying authorities put a price on his head, Williams and his elephants faced his most perilous test. In a Hollywood-worthy climax, Elephant Company, cornered by the enemy, attempted a desperate escape: a risky trek over the mountainous border to India, with a bedraggled group of refugees in tow. Elephant Bill's exploits would earn him top military honors and the praise of famed Field Marshal Sir William Slim.’

So, what are the non-fiction book you’d recommend for those with an inquiring mind? What was the last terrific non-fiction book you read? And what did you find that was suitable for your patriarchal parent this Father's Day?

|

| Another man reading. (Also not my father.) |

This week’s Word of the Weekis hermeneutic, meaning interpretive, thought to be a Latinised form of the Greek hermeneutikos, of or for interpreting, from hermeneutes, interpreter, and hermeneuein, to interpret (usually languages) into words, or to give utterance to.

Wow, Zoë, that's quite a stack you've shown us. Once again you've amazed me with your voracious range of knowledge. I'm certain that if I hurried to complete all eight books, you'll have read 16 more by then. As I said, Wow.

ReplyDeleteYour piece did get me to thinking about the unconscious judgments children make of parents in selecting gifts for them. For example, what pray tell, should I make of my son's choice of gift for me? I now have a subscription that allows me to use my computer in Greece to watch Major League Baseball! Does that mean he thinks I'm an inveterate fan of the sport (not since Roberto Clemente died), OR is it his subtle suggestion that the old man should take it up again, in place of more vigorous pursuits that lay (or would "lie" be a better choice here?) along Mykonos beaches by day, and its alleyways at night?

No matter, I love his choice, and am deeply honored to be called a father by my wonderfully thoughtful children--as opposed to the "mother" I so often hear cast my way by Greek drivers. :)

Happy Father's Day to all.

"Churchill's Ministry of Ungentlemanly Warfare" by Giles Milton. A look at the founding of the SOE and some of the missions they ran during WWII. Delightfully, bonkersly British in part, it doesn't gloss over what we were up against and shines a light on the bravery and ingenuity of those who fought from the shadows. A really good read.

ReplyDeletezoe, given whereI am: Ross King’s Brunelle’s Dome and Michelangelo and the Pope’s Ceiling. But your dad might prefer Dava Sobel’s Longiitude. All page turners.

ReplyDelete