One cop says, “Read him his rights.”

Or “Mirandize him.”

And his partner turns to the suspect and breaks into a litany that begins, “You have the right to remain silent.”

But do you know the origin of all that?

If you do, scroll down to below the second cartoon.

If not, keep reading.

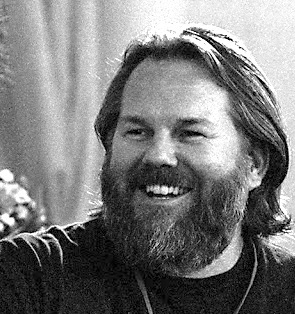

It all started with this guy, Ernesto Arturo Miranda.

In March of 1963, Miranda was busted by the cops in Phoenix, Arizona, on a charge of rape. They told him he’d been positively identified by the victim.

They were lying.

But it caused him to confess, and he was convicted.

His lawyers appealed, arguing that he hadn’t been informed of his right to remain silent, a clear violation of his civil rights.

To Miranda's surprise, and probably even to their own, they ultimately managed to bring the case before the United States Supreme Court.

Where the justices, depicted in this photograph of the time, agreed with them in a 5:4 decision.

It was handed down on the 13th of June, 1966, and read, in part:

“The person in custody must, prior to interrogation, be clearly informed that he has the right to remain silent and that anything he says will be used against him in court; he must be clearly informed that he has the right to consult with a lawyer and to have the lawyer with him during interrogation, and that, if he is indigent, a lawyer will be appointed to represent him.”

As a result of the ruling, police departments in the United States started issuing “Miranda Cards” containing a text designed to be recited to suspects prior to interrogation. The cards generally look like this:

Not surprisingly, confessions, after the introduction of Miranda Cards, dropped-off drastically.

Which, in turn, forced law-enforcement in the United States to focus, more and more, upon forensic evidence in order to get convictions.

The Brazilian Supreme Court has never handed down anything like a Miranda Decision.

So, here in Brazil, things are a bit different.

Our cops remain free to obtain convictions the old-fashioned way.

They still rely heavily on confessions.

And they still practice what used to be called “the third degree”.

Just like American cops did before Miranda:

“I'll start by saying I am no expert on South American law enforcement. That said, after reading this book I have the distinct impression the author isn't either. Depictions of crime scene investigations are sparse if explained at all. In the era of shows like CSI and Law and Order, authors should be expected to at least pretend they did some research on police procedure and present a believable investigation.”

Whoa!

A bit of ethnocentrism here perhaps?

Listen, lady, I live here, and for me, everything in that book (Blood of the Wicked) is very believable.

Lesson: Don't shoot your mouth off until you know what you're talking about.

It tends to make you look stupid.

A footnote: The State of Arizona retried Miranda and managed to obtain a conviction without making use of his confession. He was sentenced to 20 years, but paroled in 1972. After his release, he got a job as a delivery driver and supplemented his income by selling autographed Miranda cards for US$ 1.50 each.

On the 31st of January, 1976, he was involved in a violent argument during a card game, received a knife wound and was pronounced dead upon arrival at the hospital. His assailant, a Mexican national, chose to exercise his right to remain silent after having been read his Miranda rights. He was released and fled to Mexico where he disappeared.

Leighton - Monday

Leighton, "Whoa!" is right. It amazes me that a person who holds such an opinion has enough brain cells to produce a coherent sentence. I imagine she posted that opinion on Amazon, or some such place. As did the woman who complained that my 17th century Spanish noblemen had names that were too long. Maybe we need to have cards printed and inserted in the books before distribution. They could say:

ReplyDeleteSELF-REVELATION WARNING

1. If you don't know what you're talking about, you have a duty to remain silent.

2. If you write stupidities when reviewing this book in a public forum, everyone will know what an idiot you are.

With that rant out of the way, I have to say the facts about Miranda's death are so ironic. I will be telling that story again and again. Thanks for so much once again for sharing such fascinating information.

It is unlikely that today's Supreme Court would have voted the same way. In 1966, Earl Warren was the Chief Justice and the Warren court was famously liberal in its opinions. Today's court is so far right that if the justices stood on a platform, they would fall off.

ReplyDeleteMiranda v. Arizona is as much about a required code of behavior for the police as it is about the rights of the accused. The current Supreme Court handed down a ruling that weakened the original decision. In typical legalese, the Court decided in June, 2010 that "criminal suspects who are aware of their right to silence and to an attorney, but choose not to "unambiguously" invoke them, may find any subsequent voluntary statements treated as an implied waiver of their rights, and which may be used in evidence." Who among us can be clear and certain about what we say when being interrogated by the police? How many people in the last fifteen months were deprived of their right to counsel because they didn't understand the language of the law?

“I'll start by saying I am no expert on South American law enforcement." This woman doesn't seem to have a nodding acquaintance with common sense, either. I like the way she frames her disclaimer, admitting that she is not an "expert" just before she makes it blatantly obvious.

Deriving meaning from context should be a default mechanism for people who claim to be readers. I came across some posts from someone who felt the necessity to belabor the obvious. When she would write a sentence such as "I read the newspaper this morning" she would consistently post it as "I read (red) the newspaper this morning." It surprises me.

Until reading the adventures of the Murder is Everywhere bloggers, I had no idea of the myriad issues beyond the actual writing of the book that you have to deal with when you launch books. I bet you hadn't considered that someone reading a book so obviously set in Brazil would miss that point.